|

0 Comments

Response to Mark Carney’s 4th Reith Lecture 2020 - From Climate Crisis to Real Prosperity28/12/2020 I’ve just been listening to this fascinating Reith Lecture by Mark Carney on the BBC.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000qkms He quite correctly identified the main features of the Climate Crisis and some of the ways many people in the worlds of finance and economics are trying to solve this presenting problem, and even to go further to build a sustainable future beyond just stabilising the climate. He is to be commended for such a salient and well-constructed series of talks, of which this one was the fourth and final one. He seems to place a lot of confidence in the ability of market mechanisms, operating alongside government policies and regulatory legislation, to provide the shift in investment required to rebalance human activities and reflect changing citizen values on the planet and sustainability. In my view, if I can be a "critical reviewer" for a moment, he gave only a partial response to the question by Tanya Steel (WWF) – about 42 minutes into the transmission – regarding the lack of valuations being placed on standing rainforests (as opposed to felled forests for land use change into agriculture). Although he mentioned Natural Capital, he expressed some concerns about using Natural Capital approaches to put a value on nature. His main concern, which has been expressed by others (including the famous environmentalist George Monbiot), is that putting a value on nature could make it easier (and more attractive) for businesses or individuals to make profits by exploiting those natural assets, in particular by converting them from capital assets into produced goods (eg cutting down trees to make wood and changing the land from forest use into more profitable agricultural use. This is a well-worn concern about Natural Capital but it can be addressed. The key thing to realise is that, in most forests, the fact that they are not valued at all as a standing capital asset makes it much easier for them to be exploited for profit than if they had a standing forest value as a capital asset. This is because the cost of the raw material is currently essentially zero and no economic damage is recognised when the trees are felled. Placing a value on the standing forest as a capital asset (Natural Capital) would make it clear that felling the trees in an unsustainable way would be destroying value, by reducing the value of that capital asset without a larger compensating value creation from that activity. The main solution is to emphasise the necessary change of priority from a “flow” model of the economy (as typified by GDP) to a “stock” model, with managing national and global Balance Sheets being more important for a sustainable future than just managing the annual flows (equivalent to a profit and loss account). Stock Flow Consistent (“SFC”) economic modelling has been around for several years, and it was a missed opportunity for Mark Carney not to mention this in his lecture. The SFC approach follows the premise that it is important to manage balance sheets as well as income and expenditure if you want your enterprise to have a long-term future. If that enterprise is an entire country (or the whole world) then we have for too long focussed almost entirely on the income and expenditure (eg GDP) and neglected the national and global balance sheets (incorporating Natural Capital). SFC modelling is, in fact, one of the most obvious things to explore as part of current moves to implement Natural Capital in National Balance Sheets (in National Systems of Accounts), and ultimately we should be maintaining and enhancing World Balance Sheets over time, including the whole of the Natural Capital of the Earth, as this is what the continued thriving of our species (and many others) depends on. For more about this concept, see WorldBalanceSheet.com Critique of willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-receive methods for valuing natural capital12/11/2020 One valid criticism of economic valuation approaches is where they are based on willingness-to-pay (to acquire the asset not currently owned) or willingness-to-accept (to accept compensation for the loss of the asset currently owned). In many cases, and especially in relation to valuing nature, there is likely to be an element of hypothetical bias in people’s answers to surveys of their willingness-to-pay or willingness-to-accept preferences.

Hypothetical bias can enter the picture because the respondent is being confronted by a contrived, rather than an actual, set of choices. Since he or she will not actually have to pay the estimated value, and has potentially very little understanding of the significance of the hypothetical scenario underlying the question, the respondent may treat the survey casually, providing ill-considered answers. A particular case of this is where the respondent is being asked about the value of a natural asset (eg natural capital comprising part of the global commons), when it is currently valued at zero and the respondent (via the global industrial supply chains) is currently not paying anything for the use (or abuse and exploitation) of that asset. These sorts of valuation methods can also be undermined by the personal circumstances of the respondent. A respondent with very small amounts of financial resources (eg income) is likely to give much smaller willingness-to-pay answers than one with much larger financial resources. Let me paint a hypothetical scenario to illustrate this. For those of you who have heard of the Biosphere 2 experiment in the 1990s, imagine a re-run of that 2-year experiment. For those unfamiliar with it, Biosphere 2 was a project where 7 volunteers lived inside a closed set of connecting bio-domes containing air, water, soil, plants etc with no inputs or outputs (wastes) allowed to enter or leave the domes, except for the sunlight falling on them and the energy ‘leakage’ out through the glass walls at night. Everything was recycled that possibly could be. In the imaginary re-run, which I’ll call Biosphere 3, because of the strict limits on availability of such materials, suppose that each inhabitant had a daily budget of financial resource, and each of the main materials required for survival was made exclusive to each “consumer” (eg with breathable air provided via breathing apparatus and personal cylinders, and exhaled air collected in similar cylinders for recycling, water provided in personalised bottles, food in personalised containers) But suppose further that this was all provided as a public good for the first six months, on a strictly need-to-consume-for-survival basis. Suppose also that some inhabitants had financial resources very different from others – say, some had $100 per day while others had $100,000 per day. In this scenario, what would willingness-to-pay or willingness-to-receive questioning and valuation methods reveal about the values of the various survival essentials? I would guess that the answers would be very different between participants with different financial resources, and they would also be very different with passage of time. On day one, probably everyone would be willing to pay almost all, if not actually 100%, of their ‘budget’ for breathable air (even if they don’t actually have to pay for it), on the basis that none of them could survive the day without breathable air, whereas everyone could survive without water or food for one day. The trouble with that is that it gives a value for breathable air of $100 for some respondents, $100,000 for other respondents. As long as this doesn’t affect the actual amounts of air, water and food provided (because they are being provided as a public good, not as a market-traded exchange) there is no problem with continuing provision. The situation would get more complicated some days later, because after some days without water, survival would become a matter of securing water as well as air, and after an important threshold of deprival, no amount of air (or money) would compensate for lack of water, without which death would follow. Therefore, everyone would be prepared to pay something for some water, even if all the rest of their budget would be allocated to breathable air in their willingness-to-pay answers. So, perhaps their willingness-to-pay valuations would represent 90% of their “budget” for air and 10% for water each day, in order to survive until the next day. Some time after that point, edible food would have to be part of their answers, to avoid theoretical death, on the basis that no amount of money, air and water can stop someone dying if they don’t have food. So perhaps their valuations of willingness-to-pay would represent 90% of the budget allocated to air, 7% to water and 3% to food each day, in order to survive to the next day. And so on. Perhaps this situation and the associated willingness-to-pay values would reach some form of stable equilibrium after, say, six months. It can easily be seen that the “values” of each of the necessities, as measured by willingness-to-pay, would vary considerably between participants, and would vary considerably over time during those first six months. Now consider the scenario that the actual costs of providing all those necessities each and every day in Biosphere 3 was a lot higher than any of the personal financial resources of the ‘poorest’ of the individual participants, but not beyond the financial resources of the ‘richest’ participants. Assume, for example, that the cost of breathable air was $50,000 per day per person, water was $30,000 and food was $10,000. Further, assume that the “provider” after the first six months changed, and was then a computer or Artificial Intelligence operating on market exchange principles (a complete contrast from providing essentials as a public good), and was unwilling (or unable) to compromise and incur a ‘loss’ on provision (eg the provider was not going to accept a lower price than the actual cost of provision). It will be clear that this is a very different state of affairs compared with the first six months of public good service provision. The willingness-to-pay answers for the poorest participants under this new model for ‘traded’ provision would now be, in fact, an irrelevant and gross under-estimate of the value of the provision, for any answers they give, even if they answer 100% of their personal budget (ie $100 per day) as the willingness-to-pay value for any one of the essentials. They simply won’t survive day one, because they don’t have sufficient financial resources to pay for the true cost of the provision of the essentials for life. Their survival during the first six months was dependant on the provider subsidising the true ‘cost of living’ (ie incurring the cost of the public goods themselves and not passing them on to the consumer). At least some of the “richer” participants might well survive the new regime for provision, but even though some of them might be able to cover the average actual costs of provision, they might not all survive the whole 2 years. For example, if there is a bidding war, and if the Artificial Intelligence has profit maximisation as its aim, its optimum market strategy might be to use its monopoly power to manipulate prices to extract the maximum revenue, even if this means only very few participants surviving to the very end of the 2 years. This might seem a very extreme scenario, contrived in order to challenge the validity and accuracy of willingness-to-pay or willingness-to-receive valuation methods. However, if you consider for a moment the overall insights derived from Kenneth Boulding’s “Spaceship Earth” conceptual writings, it doesn’t take a huge leap of the imagination to see how the whole of the Earth can be thought of as a larger version of Biosphere 3. In fact, the reason the 1990’s dome experiment was called Biosphere 2 was because it’s designers considered the Earth to be “Biosphere 1”. So, Biosphere 1 (the current Earth we live on) has some similarities with Biosphere 3. The Earth is a finite, closed system, except for the sunlight falling on it (and the solar energy escaping through the atmosphere into space). The main differences between the Earth (Biosphere 1) and my hypothetical, imaginary Biosphere 3 are matters of scale, the key ones being the overall size of the Earth and its biological and chemical systems, and the size of the global human population. With this perspective in mind, my “Biosphere 3” thought experiment can be seen to challenge the willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-receive valuation methods used in Biosphere 1 (the Earth we live in). The Biosphere 3 scenario highlights the downsides of a marginalist approach to valuation. Willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-receive approaches are difficult to apply without the respondents falling into a marginalist perspective. That is, they are very likely (even if subconsciously) to consider a price or value in a way that is heavily influenced by their current circumstances and by the existing state (and prices / values) of the objects in the existing systems of supply (whether market-based or public goods provision). Many of these existing prices / values are effectively zero or heavily subsidised in current global supply chains, so this is likely to give a very strong bias towards very low valuations resulting from these methods of valuation. The consultation is a first step in the right direction. It sets out the proposed new legislation as a means to make supply chains more sustainable, by requiring large companies to undertake due diligence on their (global) supply chains regarding the sustainability of the harvesting of commodities (eg timber) from forests. However, inevitably this will initially fall short of being optimum for sustainability. This is because it is currently expressed in a form that represents a type of "weak sustainability".

Thresholds (for the scope of the legislation) should be set to cover a specific proportion of the amount of forest risk commodities involved in the UK economy. Those thresholds and proportions should be reviewed and revised every few years, and progressively tightened until the point of diminishing ecological returns. I believe in "strong sustainability" and would recommend moving as swiftly as possible from the initial position to a position where the sum total of the world's natural capital is maintained and improved to a point of being optimal. This will go beyond many nations' existing laws, and will need to be backed up by new international laws. Land

In this article, I will argue that land, one of the most important but scarce (ie finite) assets on the planet, is undervalued and over-exploited. This is one of the key reasons we face continuing degradation of the biosphere, damaging the long-term sustainability of ecological systems and therefore threatening our own ability to survive and thrive in perpetuity. But I will also point out that some of the key building blocks for addressing this set of challenges are already in place. All we need to do is link up the disciplines of sustainability, ecology, accountancy and economics in a quest to place proper values on the assets and obligations associated with land ownership. But let’s start by looking at definitions. There is a high degree of consensus, in language dictionaries, on the definition of land, as shown by the following two examples: “The surface of the earth that is not covered by water” (Cambridge English Dictionary) “The part of the earth’s surface that is not covered by water” (Oxford English Dictionary) Although quite simple, these definitions are helpful in some ways, but unhelpful in others. Defining land by what it is not (not covered by water) helps to some extent with a ‘first approximation’ when assessing a part of the earth’s surface. We can ask “is it covered by water?” If the answer is “no” then it is, by definition, land. On the other hand, how far does the “land” extend below the surface (down through the soil and rock) or, for that matter, above the surface (up through the atmosphere and into space)? And does it include the living organisms that inhabit the land, the soil, the non-oceanic water and the air? Wikipedia gives us a rather more descriptive (if more wordy) definition, based on economics, and some inkling of key challenges surrounding ownership: “In economics, land comprises all naturally occurring resources as well as geographic land. Examples include particular geographical locations, mineral deposits, forests, fish stocks, atmospheric quality, geostationary orbits, and portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Supply of these resources is fixed ... Because no man created the land, it does not have a definite original proprietor, owner or user. “No man made the land. It is the original inheritance of the whole species.” (John Stuart Mill) As a consequence, conflicting claims on geographic locations and mineral deposits have historically led to disputes over their economic rent and contributed to many civil wars and revolutions.” There follows a quite typical current “economic” view on land and how it is treated in most economic calculations. Excerpts from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/land.asp -------- excerpts start ------------------------- Land By JAMES CHEN Updated Jun 4, 2020 What Is Land? Land, in the business sense, can refer to real estate or property, minus buildings, and equipment, which is designated by fixed spatial boundaries. Land ownership might offer the titleholder the right to any natural resources that exist within the boundaries of their land. Traditional economics says that land is a factor of production, along with capital and labor … Land qualifies as a fixed asset instead of a current asset. ... More Ways to Understand Land In Terms of Production The basic concept of land is that it is a specific piece of earth, a property with clearly delineated boundaries, that has an owner. You can view the concept of land in different ways, depending on its context, and the circumstances under which it's being analyzed. In Economics Legally and economically, a piece of land is a factor in some form of production, and although the land is not consumed during this production, no other production - food, for example - would be possible without it. Therefore, we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production. [I’ll provide a criticism of this interpretation below] Despite the fact that people can always change the land use to be less or more profitable, we cannot increase its supply. Characteristics of Land and Land Ownership Land as a Natural Asset Land can include anything that's on the ground, which means that buildings, trees, and water are a part of land as an asset. The term land encompasses all physical elements, bestowed by nature, to a specific area or piece of property - the environment, fields, forests, minerals, climate, animals, and bodies or sources of water. A landowner may be entitled to a wealth of natural resources on their property - including plants, human and animal life, soil, minerals, geographical location, electromagnetic features, and geophysical occurrences. Because natural gas and oil in the United States are being depleted, the land that contains these resources is of great value. In many cases, drilling and oil companies pay landowners substantial sums of money for the right to use their land to access such natural resources, particularly if the land is rich in a specific resource. … Air and space rights - both above and below a property - also are included in the term land. However, the right to use the air and space above land may be subject to height limitations dictated by local ordinances, as well as state and federal laws. … Land's main economic benefit is its scarcity. The associated risks of developing land can stem from taxation, regulatory usage restrictions … and even natural disasters. ------- excerpts end ---------- I would take strong exception to Chen’s statement that “we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production”. This treatment of land would be to grossly abuse it and under-value it, both in pure economic terms but also in terms of encouraging accelerating environmental degradation. In direct contrast to Chen’s description of land’s role in production, I would argue that land needs to be restored and maintained in a sustainable state that not only supports any economic production that relies upon it, but also so that the land performs, in perpetuity, its proper role as part of earth’s living biosphere. Accounting Guidance The International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”), and the International Accounting Standards (“IAS”) set the international frameworks guiding all accountants around the world in what is deemed to be acceptable ways of accounting for everything that appears in a balance sheet or a profit and loss statement. An example is the way assets are valued and reported. There are a number of accepted ways of attributing, or calculating, a value for an asset, including “land”. In accounting guidance, land is included in “property, plant and equipment”, being a particular type of “property”. Excerpt from IAS 16 ---------------------------- Property, plant and equipment are tangible items that: (a) are held for use in the production or supply of goods or services, for rental to others, or for administrative purposes; and (b) are expected to be used during more than one period. The cost of an item of property, plant and equipment shall be recognised as an asset if, and only if: (a) it is probable that future economic benefits associated with the item will flow to the entity; and (b) the cost of the item can be measured reliably. If the cost of land includes the costs of site dismantlement, removal and restoration, that portion of the land asset is depreciated over the period of benefits obtained by incurring those costs. Excerpts end ---------------------- From the excerpts above, we can build on what I have said about the obligation to maintain land to fulfil its role as part of a sustainable living biosphere. All that is required is to establish, and enforce, the principle of holding owners of land to account for maintaining the land sustainably. This needs to be backed up by national and international governance mechanisms (eg national and international laws and environmental regulations). When those governance measures are in place, then the asset value of any piece of land an owner wants to hold will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner. If the land’s current state is a long way below that which would be considered biospherically sustainable, then the value of the land might even be negative, because although the owner has an asset that will produce some positive economic value, for example from agricultural produce generated from it, there could exist a large obligation (liability) to set against that, representing the amount the current owner needs to spend to restore the land to a biospherically sustainable state. If the liability is larger than the value of the economic productivity of the land, then the land (asset) net value will be negative. It follows that the market price of any piece of land an owner wants to sell will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner and also the same obligation on the new owner. It is probably quite clear that, in the paragraphs above, I’ve based my arguments on a definition of strong sustainability when using the terms “sustainable” and “sustainability” etc. Pairs of air jets could do the trick - for more info see my article on my "Ideas in a Nutshell" page.

Just discovered the work of Anna Rosling on "Dollar Street" - a visualisation of people's lives around the world, enabling us to see how people on a spectrum by income really live.

Here's the link: https://www.gapminder.org/dollar-street/matrix?thing=Homes&countries=World®ions=World&zoom=4&row=1&lowIncome=481&highIncome=843&lang=en The website also includes a TED talk by Anna, which explains how the material was collected and how it helps us to understand the similarities and differences generated by income and geography. Global sustainability will only happen if the mainstream of the population live lives that are sustainable. That might seem like a trivial statement. But it has some fundamental questions underneath it. How and when will the mainstream accelerate the necessary shift from an unsustainable trajectory to a sustainable one?

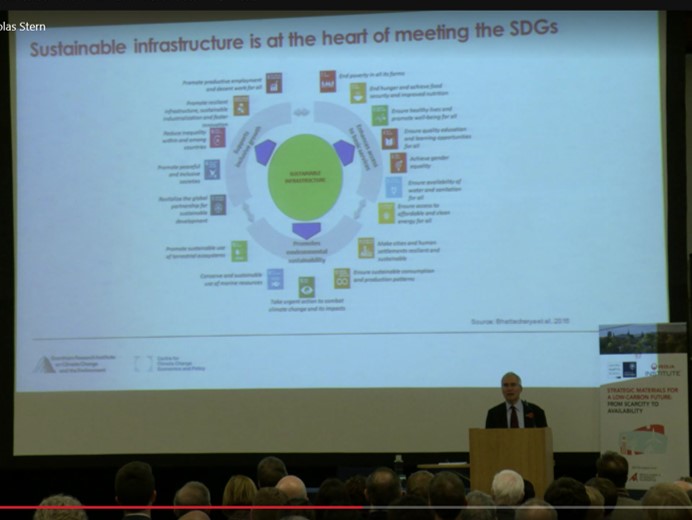

The transition has started, but is not happening fast enough, as highlighted by Lord Stern in many talks and publications in the last few years, on the issue of Climate Change alone. And yet it goes much further than Climate Change. It is an issue of water, food, land use, consumerism. All these aspects require major shifts globally to achieve a just and sustainable future for all global citizens. The mainstream is the place where this shift will really happen. And if the mainstream doesn't "move" in the sense of changing its ways of living, travelling, earning, using energy, consuming, recycling, then the mainstream might have to "move" in a different sense - to physically move to find different places to sustain itself as increasingly dramatic deterioration happens in the places they currently live - resulting in mass migration on an unprecedented scale. I wasn't able to attend this talk in person in Oxford earlier this month, but I caught the tail-end via the livestream video, and watched the whole of it later (link here). Lord Stern is optimistic, and points out that this is a topic where there is massive potential for cross-party support. He paints a picture of short-term investment in sustainable infrastructure to provide economic growth while moving to a net zero carbon economy in the next 40 - 50 years, supported by the Sustainable Development Goals. Urgency and scale of the transition were key emphases in his talk. We're moving much too slowly on this, and we need to speed up.

Here is a pdf (opens in new window) of about 40 questions and answers from an exercise I did this month by allowing a group of about twenty 10 to 15 year olds to text me their questions about the environment. As you'll see, some of them didn't keep strictly on-topic. However, I managed to weave most of the answers back onto the subject.

Video of an excellent summary about Natural Capital by Dieter Helm at Irish Natural Capital Forum October 2016 here.

I didn't attend myself, but the video records Professor Helm's 30-min talk and Q&A. Prof Helm is Chair of the UK's Natural Capital Committee. Some wonderful soundbites, eg "No country in Europe currently has a Balance Sheet" (9mins 30). and "better to be roughly right than precisely wrong" (11 mins 45 to 12 mins 15). Accountancy isn't just for business, it's for the environment" (About 20 mins). The UK's Natural Capital Committee continues to advise Government on how the 25 Year Environment Plan can be created in such a way that the environment we leave to our children is no worse than the one we inherited ourselves.

The Committee's 2017 report on this can be found here. The Planetary CFO will be keeping an eye on how the 25 year plan shapes up, because merely stopping the decline is not going to be good enough in the longer-term. We will need a co-ordinated world-wide plan for the environment globally, for a sustainable environment to provide well for peak global population of, perhaps, 10 billion. So-called "health tourism" is in the news a lot, painted as a large problem in the UK. The Planetary CFO's answer to this is that it wouldn't be such a large problem if a Global Health Insurance scheme was in place, agreed between all countries of the world, along similar lines to National Insurance in the UK. A global scheme would start providing basic health and wellbeing services for all global citizens, from the moment of birth (irrespective of the place of birth) and in any place in the world where they are at the time they need those services. A hospital in one county in England doesn't refuse treatment to someone who lives in another county, so why should we draw such distinctions for people from other countries?

A Global Health Insurance scheme would generate larger flows of money into the health systems of the world, which would provide larger resources for maintenance and investment, for example for scaling up to reduce waiting times, or expanding provision geographically. Investment in health facilities funded by such increased money flows would strengthen the assets within the non-natural capital section of the World Balance Sheet, making it easier to provide basic health and welfare services to all global citizens. When we say we value something, it usually means we’d rather not lose it, or lose the access to it or the ability to experience it. Or perhaps we gain something from being able to use it, and we lose something if we lose the use of it. And the more difficult it would be to restore it or replace it, the higher the value we would place on it, perhaps. This multiplicity of perspectives gives rise to a variety of ways of “placing a value on it”. For example, a monetary value we ascribe to an object might represent: · The original cost of producing it, if we made it ourselves – including amounts for our time and effort as well as all the raw materials, energy and other inputs to the processes used (historic cost) · The amount we paid for it if we bought it rather than making it ourselves (purchase cost) · The cost of replacing it if it is lost or destroyed (replacement cost) · The cost of alternative means of satisfying the same need or desire that it fulfils (a substitution value) · The money that could be obtained by preparing it for sale and then selling it (realisable value) · The price at which it can be bought or sold in its current state in a perfect market (market value) · The amount we could claim from an insurance company if it was lost in an incident covered by insurance (insured value) · The total of all the future discounted cash in-flows and out-flows generated by the expected future use of the object until it reaches the end of its useful life (the Net Present Value, or economic value) Of course, in most circumstances, for a specific object, all of the above approaches would result in a different value being ascribed. The method we use therefore becomes very context-dependent. In a sustainability context, the most concerning disjoint between such valuations would occur when someone owning or controlling a part of the Natural Capital places the wrong kind of value on it. For example, rainforest that has taken millennia to evolve and achieve a balanced and healthy ecosystem state should be valued at replacement cost, which is very high because of the immense amount of time and effort that would be required to replicate the patient construction of the ecosystem by nature. The realisable value or market value might be much lower because there is much less effort and time required to cut down the trees and sell the wood to someone than there is to grow a healthy ecosystem. Therefore, the method of valuation chosen very much depends on the purpose for which it is being done. There is a big difference between approaches appropriate for valuing something for the purposes of maintaining it within healthy ecosystems, within a sustainable custodianship role and approaches for valuing something for the purposes of serving market objectives or generation of business profits. Valuing such assets at replacement cost, but only while they remain in their natural state, and valuing them at a substitution cost if they are removed from that ecosystem (eg by being cut down and converted into raw materials) is necessary. This prevents the Tragedy of the Commons, by ensuring that as essential natural assets become scarcer, they become more and more highly valued for the purposes of conservation, and less and less valuable for the purposes of being converted for alternative use outside the ecosystem. That duality of perspectives on the same object is a necessary step in order to reconcile the need for conservation alongside the need for sustainable harvesting and use of resources in sustainable ways for humanity to co-exist successfully with natural ecosystems in perpetuity. An important part of this consideration is clearly the question of who owns or controls assets, which is linked to who is allowed to own or control them. The Global Commons (eg the air we breathe, the water we drink, the basic food that sustains us, the ecosystems that provide some of these, and so on), because of their essential role in maintaining sustainability of life on Earth, cannot be allowed to be owned or controlled by interests that would breach sustainability limits. The global custodian could legitimately fine anyone who converted such assets (eg by cutting them down for wood) by charging them the difference between the replacement cost and the substitution cost (as described above). A proviso on this is that there exists the means to apply the revenue from such fines to undertake that patient replacement activity, while what remains of the assets of that type is sufficient to maintain ecosystems within sustainable ranges. The success of this approach depends on adequate prevention, detection and policing of acts giving rise to such fines. Part of the deterrence would be the size of the fines resulting from the above methods of calculation. |

AuthorThe Planetary CFO - working towards a sustainable World Balance Sheet. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|