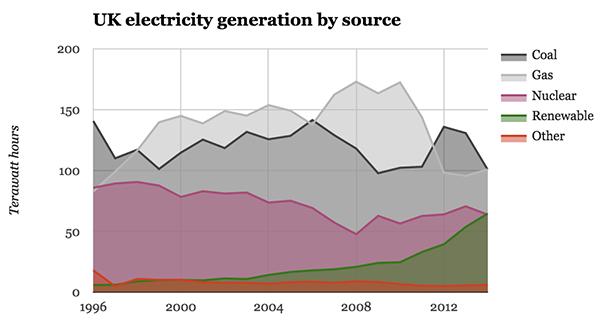

This diagram is part of the reason I'm happy to use an Electric Vehicle in the UK - The mix of energy generation which provides the electricity I charge it with is moving rapidly from fossil fuels to renewables, from high carbon emmitting sources to low or zero emitting sources. Also, I have solar panels on my house, so some of the time I'm using locally generated electricity to charge the car rather than drawing it from the grid.

0 Comments

So-called "health tourism" is in the news a lot, painted as a large problem in the UK. The Planetary CFO's answer to this is that it wouldn't be such a large problem if a Global Health Insurance scheme was in place, agreed between all countries of the world, along similar lines to National Insurance in the UK. A global scheme would start providing basic health and wellbeing services for all global citizens, from the moment of birth (irrespective of the place of birth) and in any place in the world where they are at the time they need those services. A hospital in one county in England doesn't refuse treatment to someone who lives in another county, so why should we draw such distinctions for people from other countries?

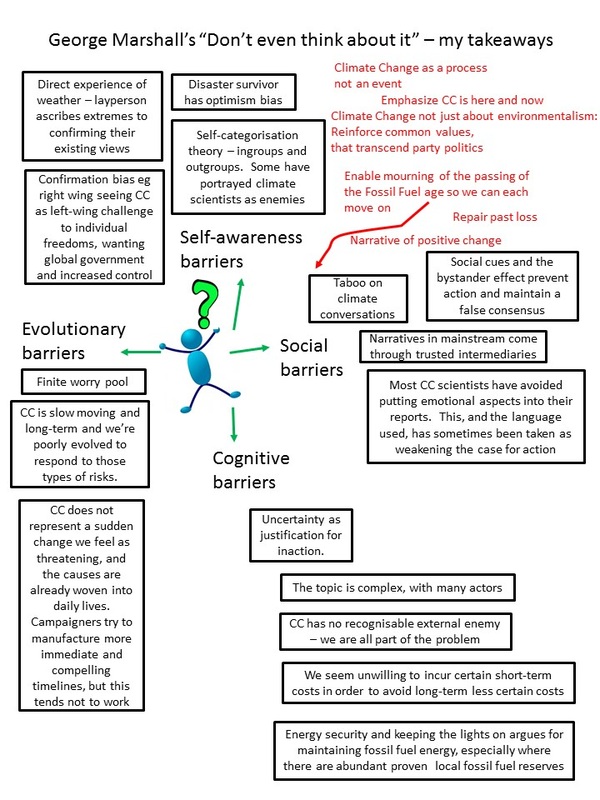

A Global Health Insurance scheme would generate larger flows of money into the health systems of the world, which would provide larger resources for maintenance and investment, for example for scaling up to reduce waiting times, or expanding provision geographically. Investment in health facilities funded by such increased money flows would strengthen the assets within the non-natural capital section of the World Balance Sheet, making it easier to provide basic health and welfare services to all global citizens. When we say we value something, it usually means we’d rather not lose it, or lose the access to it or the ability to experience it. Or perhaps we gain something from being able to use it, and we lose something if we lose the use of it. And the more difficult it would be to restore it or replace it, the higher the value we would place on it, perhaps. This multiplicity of perspectives gives rise to a variety of ways of “placing a value on it”. For example, a monetary value we ascribe to an object might represent: · The original cost of producing it, if we made it ourselves – including amounts for our time and effort as well as all the raw materials, energy and other inputs to the processes used (historic cost) · The amount we paid for it if we bought it rather than making it ourselves (purchase cost) · The cost of replacing it if it is lost or destroyed (replacement cost) · The cost of alternative means of satisfying the same need or desire that it fulfils (a substitution value) · The money that could be obtained by preparing it for sale and then selling it (realisable value) · The price at which it can be bought or sold in its current state in a perfect market (market value) · The amount we could claim from an insurance company if it was lost in an incident covered by insurance (insured value) · The total of all the future discounted cash in-flows and out-flows generated by the expected future use of the object until it reaches the end of its useful life (the Net Present Value, or economic value) Of course, in most circumstances, for a specific object, all of the above approaches would result in a different value being ascribed. The method we use therefore becomes very context-dependent. In a sustainability context, the most concerning disjoint between such valuations would occur when someone owning or controlling a part of the Natural Capital places the wrong kind of value on it. For example, rainforest that has taken millennia to evolve and achieve a balanced and healthy ecosystem state should be valued at replacement cost, which is very high because of the immense amount of time and effort that would be required to replicate the patient construction of the ecosystem by nature. The realisable value or market value might be much lower because there is much less effort and time required to cut down the trees and sell the wood to someone than there is to grow a healthy ecosystem. Therefore, the method of valuation chosen very much depends on the purpose for which it is being done. There is a big difference between approaches appropriate for valuing something for the purposes of maintaining it within healthy ecosystems, within a sustainable custodianship role and approaches for valuing something for the purposes of serving market objectives or generation of business profits. Valuing such assets at replacement cost, but only while they remain in their natural state, and valuing them at a substitution cost if they are removed from that ecosystem (eg by being cut down and converted into raw materials) is necessary. This prevents the Tragedy of the Commons, by ensuring that as essential natural assets become scarcer, they become more and more highly valued for the purposes of conservation, and less and less valuable for the purposes of being converted for alternative use outside the ecosystem. That duality of perspectives on the same object is a necessary step in order to reconcile the need for conservation alongside the need for sustainable harvesting and use of resources in sustainable ways for humanity to co-exist successfully with natural ecosystems in perpetuity. An important part of this consideration is clearly the question of who owns or controls assets, which is linked to who is allowed to own or control them. The Global Commons (eg the air we breathe, the water we drink, the basic food that sustains us, the ecosystems that provide some of these, and so on), because of their essential role in maintaining sustainability of life on Earth, cannot be allowed to be owned or controlled by interests that would breach sustainability limits. The global custodian could legitimately fine anyone who converted such assets (eg by cutting them down for wood) by charging them the difference between the replacement cost and the substitution cost (as described above). A proviso on this is that there exists the means to apply the revenue from such fines to undertake that patient replacement activity, while what remains of the assets of that type is sufficient to maintain ecosystems within sustainable ranges. The success of this approach depends on adequate prevention, detection and policing of acts giving rise to such fines. Part of the deterrence would be the size of the fines resulting from the above methods of calculation. I few months ago, I read George Marshall's book "Don't even think about it - why our brains are wired to ignore climate change". It's taken me a while to collect my thoughts about the book. In fact, I couldn't really sort them out in a linear way. So I drew up the slide below, and in the process the points I captured shifted around the page as I worked on them, turning them over in my mind and relating them to other points. What emerged in my mind were four groupings of things that seemed to naturally go together. I then labelled each group - self-awareness barriers, social barriers, cognitive barriers and evolutionary barriers. The red text that I then added were some key points for what we can do to move things forward in a positive direction. What then occurred to me was that taking the initiative to break through brings most people up against the taboo on climate conversations. However, if this proves a severe barrier, perhaps an easier "in" is to gently prompt the audience for such initiatives to make themselves space and time to do their own investigations of these four groups of barriers preventing them from finding a better life for themselves and those around them who they know and love. That way, the audience would stand a chance of meeting the communicator of climate change and engaging in a conversation that can go somewhere. Just my perspective on what I got from the book. I hope it might help others. The only reference to finance in my summary is the tendency among many people to avoid short-term costs even when this means there will be far greater costs in the longer-term, because there is some level of uncertainty surrounding these longer-term costs.

We hear a lot about efficiency, but not enough about circular economy. Which is strange, because circular economy is a no-brainer in my view. Starting a conversation with efficiency is starting in the wrong place, in a use-it-up and throw-it-away kind of place. Starting a conversation with circular economy starts it in a better place.

First we had recycle, when we knew we had to reduce the amount of stuff being "thrown away", usually into landfill. Then we had repair and recycle. Why throw it away at all if you could repair it, delaying the inevitable moment when it would have to be thrown away? Then we had reuse, repair and recycle, when we could turn an existing object to a new use, or repurpose it, when it was no longer suitable for its previous use. Then we had reduce - use less of something - less in equals less to throw away at the end. All these were about efficiency - reducing the amount thrown away for each unit of material that was an input to produce a thing we first started to use. So we had reduce - reuse - repair - recycle. Now we need to reconceive - to re-imagine the whole. Not just the inputs and outputs from a process, but a holistic approach to our need/want and how it is satisfied (or redirected) between self and surroundings. That's what will bring a circular economy. When the first question is about the relationship between self and non-self. Between Me and Us and All (all living things, all material things and the only world we will ever fully experience - the planet). In this re-imagining, we are not only served by the circular economy, but we are also a servant to it as well. In the same way that there are numerous symbioses in nature, we are part of the circular economy, contributing to it as well as receiving from it. This is a new mindset. One that will help us find a sustainable future together, rather than a narrow, efficient but ultimately unsustainable one. |

AuthorThe Planetary CFO - working towards a sustainable World Balance Sheet. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|