|

Linked here, this podcast is an excellent summary of the interplay between climate change and UK politics.

Response to Mark Carney’s 4th Reith Lecture 2020 - From Climate Crisis to Real Prosperity28/12/2020 I’ve just been listening to this fascinating Reith Lecture by Mark Carney on the BBC.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000qkms He quite correctly identified the main features of the Climate Crisis and some of the ways many people in the worlds of finance and economics are trying to solve this presenting problem, and even to go further to build a sustainable future beyond just stabilising the climate. He is to be commended for such a salient and well-constructed series of talks, of which this one was the fourth and final one. He seems to place a lot of confidence in the ability of market mechanisms, operating alongside government policies and regulatory legislation, to provide the shift in investment required to rebalance human activities and reflect changing citizen values on the planet and sustainability. In my view, if I can be a "critical reviewer" for a moment, he gave only a partial response to the question by Tanya Steel (WWF) – about 42 minutes into the transmission – regarding the lack of valuations being placed on standing rainforests (as opposed to felled forests for land use change into agriculture). Although he mentioned Natural Capital, he expressed some concerns about using Natural Capital approaches to put a value on nature. His main concern, which has been expressed by others (including the famous environmentalist George Monbiot), is that putting a value on nature could make it easier (and more attractive) for businesses or individuals to make profits by exploiting those natural assets, in particular by converting them from capital assets into produced goods (eg cutting down trees to make wood and changing the land from forest use into more profitable agricultural use. This is a well-worn concern about Natural Capital but it can be addressed. The key thing to realise is that, in most forests, the fact that they are not valued at all as a standing capital asset makes it much easier for them to be exploited for profit than if they had a standing forest value as a capital asset. This is because the cost of the raw material is currently essentially zero and no economic damage is recognised when the trees are felled. Placing a value on the standing forest as a capital asset (Natural Capital) would make it clear that felling the trees in an unsustainable way would be destroying value, by reducing the value of that capital asset without a larger compensating value creation from that activity. The main solution is to emphasise the necessary change of priority from a “flow” model of the economy (as typified by GDP) to a “stock” model, with managing national and global Balance Sheets being more important for a sustainable future than just managing the annual flows (equivalent to a profit and loss account). Stock Flow Consistent (“SFC”) economic modelling has been around for several years, and it was a missed opportunity for Mark Carney not to mention this in his lecture. The SFC approach follows the premise that it is important to manage balance sheets as well as income and expenditure if you want your enterprise to have a long-term future. If that enterprise is an entire country (or the whole world) then we have for too long focussed almost entirely on the income and expenditure (eg GDP) and neglected the national and global balance sheets (incorporating Natural Capital). SFC modelling is, in fact, one of the most obvious things to explore as part of current moves to implement Natural Capital in National Balance Sheets (in National Systems of Accounts), and ultimately we should be maintaining and enhancing World Balance Sheets over time, including the whole of the Natural Capital of the Earth, as this is what the continued thriving of our species (and many others) depends on. For more about this concept, see WorldBalanceSheet.com Steady State Economics might not be the best answer to current and future sustainability challenges. It might not even be sufficient as a solution, in its current form, as advocated by CASSE (The Centre for Advancement of Steady State Economics).

It might, however, be a useful stepping stone to better solutions we can’t yet know about, let alone express in economic terms. Some of the work of Brian Czech, Director of CASSE, and other authors in “Best of the Daly News” (ie Czech, 2020) is examined further below and in my forthcoming book, due to be published in 2021. And SSE might be a whole lot better than the current way economies are managed (or left to markets) in most parts of the world today. However, it's worth setting some wider context first, which will help to explain why this, and other new forms of economic thinking, are a necessary field of thought and practice to address our current predicament. The Bottleneck humanity hopes to pass through “The Precipice” by Toby Ord (ie Ord, 2020) resonates with my own perspectives on the long-term development of humanity and the risks it currently faces. Ord points out that humanity is at a critical crossroads, where its power has outstripped its wisdom, resulting in several serious existential risks (including unsustainability of our impacts on nature, rogue AI (Artificial Intelligence), engineered biological agents and conflicts that might, potentially, involve nuclear weapons). The finite planetary limits of the biosphere that supports us are like a bottle containing a model ship in the classic “ship in a bottle”. Our population and civilisation are like the ship. The human ecological footprint has been growing as we have developed (the ship has been growing in size and complexity inside the bottle). But we are realising that the finite bounds of the biosphere, and the damage caused by our overshooting sustainable thresholds, is reducing the size of the biosphere and its capacity to support us (the neck of the bottle has been narrowing, as a result of our actions) and the rate of that depletion in biospherical capacity is accelerating. We want humanity to progress further, because our future potential is immense if we can more effectively harness the energy from the sun (the only input from outside the bottle) and if we can access materials from outside the earth system, for example by mining materials on the moon, from asteroids or find even more distant exploitable resources. After all, the universe outside the bottle is potentially infinite in materials, energy and evolutionary progress for living beings. Our challenge is to pass through the neck of the bottle, and to pull what we can of the ship, through with us, without destroying the bottle that is humanity’s birthplace. It becomes obvious there are two main options for doing this, which are not mutually exclusive. Firstly, we can modify our impacts on the natural biosphere, to reduce (and eventually reverse) the rate of degradation of the biosphere’s capacity to support us (slow down, and then reverse, the rate at which the neck of the bottle is shrinking). Secondly, we can alter our civilisation and the way it draws resources from the biosphere and uses them, for example adopting circular systems of material and energy flow, such as those advocated in circular economy, or even implementing something along the lines of a steady state economy, a GDP-growth-agnostic economy or something similar (remodel the ship so it will more easily pass through the neck). If we can do these things, a bright future awaits and the innumerable future generations of humanity will thank us for our efforts. If we fail, however, our failure will go down in history as the biggest failure of any known life reaching a state of advanced intelligence and civilisation. We should use the sense of responsibility this imparts as a spur to action. The bottleneck analogy is used also, extensively, in White and Hagens (2020) “The Bottlenecks of the 21st Century”. I've just published the World Balance Sheet 2018 here. This is an illustrative example intended to spark debate and ideas, rather than a finished or perfect object. Very few people have even attempted to create such a balance sheet. I've built on the work of one of those who has - Harald Deutsch - amending it and enhancing it through a lens of sustainability, for example by adding in natural capital. What my world balance sheet shows is that there is a significant "asset stewardship shortfall" of about USD 600 trillion. This arises mostly from degradation, and drawing down, of natural capital to meet humanity's aggregate consumption. I think the overall message is clear - we need to repair, enhance and maintain adequate natural capital to reduce the asset stewardship shortfall and eventually restore the balance in the world balance sheet.

The consultation is a first step in the right direction. It sets out the proposed new legislation as a means to make supply chains more sustainable, by requiring large companies to undertake due diligence on their (global) supply chains regarding the sustainability of the harvesting of commodities (eg timber) from forests. However, inevitably this will initially fall short of being optimum for sustainability. This is because it is currently expressed in a form that represents a type of "weak sustainability".

Thresholds (for the scope of the legislation) should be set to cover a specific proportion of the amount of forest risk commodities involved in the UK economy. Those thresholds and proportions should be reviewed and revised every few years, and progressively tightened until the point of diminishing ecological returns. I believe in "strong sustainability" and would recommend moving as swiftly as possible from the initial position to a position where the sum total of the world's natural capital is maintained and improved to a point of being optimal. This will go beyond many nations' existing laws, and will need to be backed up by new international laws. I participated in an A4S webinar yesterday on "Measure What Matters: Capitals Accounting". It was an excellent opportunity to engage with a network of CFOs on some of the big issues relevant to accounting and sustainability.

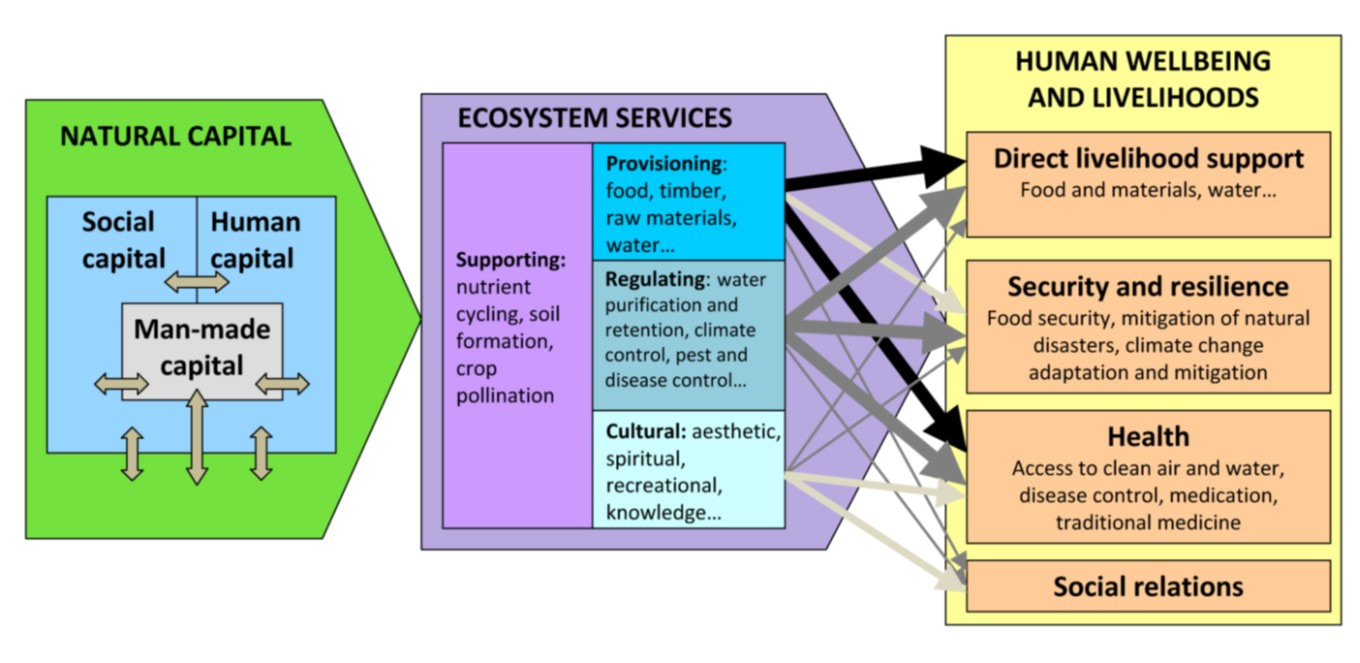

One of the discussion points was about substitutability of capitals, and, in particular, whether Natural Capital should be substitutable for other forms of capital. For context, the diagram above is from TEEB (2018) "Measuring what matters in agricultural food systems". The diagram was adapted by the authors of TEEB (2018) from an original source, which was the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 Synthesis Report. The general view from the webinar leaders/panelists, including a representative from TEEB, was that Natural Capital should not be substitutable for other types of capital. Full stop. No ifs, no buts. Natural Capital should be maintained (even enhanced) and not converted into other types of capital (for example, produced capital or financial capital). This draws on (and is almost a definition of) a concept of Strong Sustainability, rather than Weak Sustainability. Strong Sustainability is a concept I support, as a suitable response to the mounting evidence that generations of people have not just neglected but caused massive amounts of destruction and degradation to Natural Capital around the world, pushing us far into ecological overshoot, as highlighted very graphically by Earth Overshoot Day. It also means that individual businesses, as well as all other types of organisation, when assessing their impacts and dependencies, should carefully and separately identify the distinctions between the goods and services which Natural Capital provides as inputs to their business models, as distinct from the Natural Capital which provides them. (This is something that many organisations have been woefully poor at doing throughout modern history). They must not degrade or deplete the Natural Capital, for example by causing goods and services drawn from Natural Capital sources to exceed that which can sustainably be produced by that Natural Capital in perpetuity. Also, they must not allow their business processes to cause more carbon emissions, other waste or damage than can be sustainably accommodated by the Natural Capital in perpetuity. At an aggregate global level, the development of a World Balance Sheet will help us to assess whether the combined activities and impacts of all organisations, whether businesses or not, are complying with these requirements. The whole of the world's Natural Capital will be a key component of the World Balance Sheet. See more about the World Balance Sheet concept in my previous blog posts and at WorldBalanceSheet.com. On that site, I list my recent books, published this year, which go into more details about the emergence of the World Balance Sheet concept. These are very early days for the World Balance Sheet, but my hope is that we will rapidly reach the point where it will tell us whether enough people are practising Strong Sustainability to make a real difference in the transition to a just and sustainable future for the whole global population, today and in perpetuity. Land

In this article, I will argue that land, one of the most important but scarce (ie finite) assets on the planet, is undervalued and over-exploited. This is one of the key reasons we face continuing degradation of the biosphere, damaging the long-term sustainability of ecological systems and therefore threatening our own ability to survive and thrive in perpetuity. But I will also point out that some of the key building blocks for addressing this set of challenges are already in place. All we need to do is link up the disciplines of sustainability, ecology, accountancy and economics in a quest to place proper values on the assets and obligations associated with land ownership. But let’s start by looking at definitions. There is a high degree of consensus, in language dictionaries, on the definition of land, as shown by the following two examples: “The surface of the earth that is not covered by water” (Cambridge English Dictionary) “The part of the earth’s surface that is not covered by water” (Oxford English Dictionary) Although quite simple, these definitions are helpful in some ways, but unhelpful in others. Defining land by what it is not (not covered by water) helps to some extent with a ‘first approximation’ when assessing a part of the earth’s surface. We can ask “is it covered by water?” If the answer is “no” then it is, by definition, land. On the other hand, how far does the “land” extend below the surface (down through the soil and rock) or, for that matter, above the surface (up through the atmosphere and into space)? And does it include the living organisms that inhabit the land, the soil, the non-oceanic water and the air? Wikipedia gives us a rather more descriptive (if more wordy) definition, based on economics, and some inkling of key challenges surrounding ownership: “In economics, land comprises all naturally occurring resources as well as geographic land. Examples include particular geographical locations, mineral deposits, forests, fish stocks, atmospheric quality, geostationary orbits, and portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Supply of these resources is fixed ... Because no man created the land, it does not have a definite original proprietor, owner or user. “No man made the land. It is the original inheritance of the whole species.” (John Stuart Mill) As a consequence, conflicting claims on geographic locations and mineral deposits have historically led to disputes over their economic rent and contributed to many civil wars and revolutions.” There follows a quite typical current “economic” view on land and how it is treated in most economic calculations. Excerpts from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/land.asp -------- excerpts start ------------------------- Land By JAMES CHEN Updated Jun 4, 2020 What Is Land? Land, in the business sense, can refer to real estate or property, minus buildings, and equipment, which is designated by fixed spatial boundaries. Land ownership might offer the titleholder the right to any natural resources that exist within the boundaries of their land. Traditional economics says that land is a factor of production, along with capital and labor … Land qualifies as a fixed asset instead of a current asset. ... More Ways to Understand Land In Terms of Production The basic concept of land is that it is a specific piece of earth, a property with clearly delineated boundaries, that has an owner. You can view the concept of land in different ways, depending on its context, and the circumstances under which it's being analyzed. In Economics Legally and economically, a piece of land is a factor in some form of production, and although the land is not consumed during this production, no other production - food, for example - would be possible without it. Therefore, we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production. [I’ll provide a criticism of this interpretation below] Despite the fact that people can always change the land use to be less or more profitable, we cannot increase its supply. Characteristics of Land and Land Ownership Land as a Natural Asset Land can include anything that's on the ground, which means that buildings, trees, and water are a part of land as an asset. The term land encompasses all physical elements, bestowed by nature, to a specific area or piece of property - the environment, fields, forests, minerals, climate, animals, and bodies or sources of water. A landowner may be entitled to a wealth of natural resources on their property - including plants, human and animal life, soil, minerals, geographical location, electromagnetic features, and geophysical occurrences. Because natural gas and oil in the United States are being depleted, the land that contains these resources is of great value. In many cases, drilling and oil companies pay landowners substantial sums of money for the right to use their land to access such natural resources, particularly if the land is rich in a specific resource. … Air and space rights - both above and below a property - also are included in the term land. However, the right to use the air and space above land may be subject to height limitations dictated by local ordinances, as well as state and federal laws. … Land's main economic benefit is its scarcity. The associated risks of developing land can stem from taxation, regulatory usage restrictions … and even natural disasters. ------- excerpts end ---------- I would take strong exception to Chen’s statement that “we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production”. This treatment of land would be to grossly abuse it and under-value it, both in pure economic terms but also in terms of encouraging accelerating environmental degradation. In direct contrast to Chen’s description of land’s role in production, I would argue that land needs to be restored and maintained in a sustainable state that not only supports any economic production that relies upon it, but also so that the land performs, in perpetuity, its proper role as part of earth’s living biosphere. Accounting Guidance The International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”), and the International Accounting Standards (“IAS”) set the international frameworks guiding all accountants around the world in what is deemed to be acceptable ways of accounting for everything that appears in a balance sheet or a profit and loss statement. An example is the way assets are valued and reported. There are a number of accepted ways of attributing, or calculating, a value for an asset, including “land”. In accounting guidance, land is included in “property, plant and equipment”, being a particular type of “property”. Excerpt from IAS 16 ---------------------------- Property, plant and equipment are tangible items that: (a) are held for use in the production or supply of goods or services, for rental to others, or for administrative purposes; and (b) are expected to be used during more than one period. The cost of an item of property, plant and equipment shall be recognised as an asset if, and only if: (a) it is probable that future economic benefits associated with the item will flow to the entity; and (b) the cost of the item can be measured reliably. If the cost of land includes the costs of site dismantlement, removal and restoration, that portion of the land asset is depreciated over the period of benefits obtained by incurring those costs. Excerpts end ---------------------- From the excerpts above, we can build on what I have said about the obligation to maintain land to fulfil its role as part of a sustainable living biosphere. All that is required is to establish, and enforce, the principle of holding owners of land to account for maintaining the land sustainably. This needs to be backed up by national and international governance mechanisms (eg national and international laws and environmental regulations). When those governance measures are in place, then the asset value of any piece of land an owner wants to hold will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner. If the land’s current state is a long way below that which would be considered biospherically sustainable, then the value of the land might even be negative, because although the owner has an asset that will produce some positive economic value, for example from agricultural produce generated from it, there could exist a large obligation (liability) to set against that, representing the amount the current owner needs to spend to restore the land to a biospherically sustainable state. If the liability is larger than the value of the economic productivity of the land, then the land (asset) net value will be negative. It follows that the market price of any piece of land an owner wants to sell will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner and also the same obligation on the new owner. It is probably quite clear that, in the paragraphs above, I’ve based my arguments on a definition of strong sustainability when using the terms “sustainable” and “sustainability” etc. Global sustainability will only happen if the mainstream of the population live lives that are sustainable. That might seem like a trivial statement. But it has some fundamental questions underneath it. How and when will the mainstream accelerate the necessary shift from an unsustainable trajectory to a sustainable one?

The transition has started, but is not happening fast enough, as highlighted by Lord Stern in many talks and publications in the last few years, on the issue of Climate Change alone. And yet it goes much further than Climate Change. It is an issue of water, food, land use, consumerism. All these aspects require major shifts globally to achieve a just and sustainable future for all global citizens. The mainstream is the place where this shift will really happen. And if the mainstream doesn't "move" in the sense of changing its ways of living, travelling, earning, using energy, consuming, recycling, then the mainstream might have to "move" in a different sense - to physically move to find different places to sustain itself as increasingly dramatic deterioration happens in the places they currently live - resulting in mass migration on an unprecedented scale. The Global Commons (eg the air we breathe, the rain water, the oceans) are too important in sustaining all the global population to let their management be left to any one political party. Climate change and other challenges are best solved by cross-party working.

It could be a mistake to attach hope for sustainability solutions to one particular party. That lends itself to people taking the view that, because they don't support that particular party, they should give up on sustainability altogether in order to demonstrate loyalty to their chosen party. Best to make sustainability non-partisan, and to work to weave it into the fibre of all political parties. Our joint future on the planet is too big a thing to be left to become a political football. I wasn't able to attend this talk in person in Oxford earlier this month, but I caught the tail-end via the livestream video, and watched the whole of it later (link here). Lord Stern is optimistic, and points out that this is a topic where there is massive potential for cross-party support. He paints a picture of short-term investment in sustainable infrastructure to provide economic growth while moving to a net zero carbon economy in the next 40 - 50 years, supported by the Sustainable Development Goals. Urgency and scale of the transition were key emphases in his talk. We're moving much too slowly on this, and we need to speed up.

Here is a pdf (opens in new window) of about 40 questions and answers from an exercise I did this month by allowing a group of about twenty 10 to 15 year olds to text me their questions about the environment. As you'll see, some of them didn't keep strictly on-topic. However, I managed to weave most of the answers back onto the subject.

Look for long-term trends rather than individual weather events as evidence of climate change8/9/2017 Hurricane Irma is wreaking devastation in the Caribbean this month. Deplorable as it is as a single extreme weather event, let's not forget that the evidence for climate change is not based on a single event such as this, but rather on a large body of evidence over long timescales.

When asked if a single weather event proves climate change, I point to the long-term data trends. That way, I can't be accused of being inconsistent when someone points to a particularly cold Winter weather event and I say "that doesn't disprove climate change - look at the long-term trends". Amory Lovins gave an excellent talk about disruptive energy technologies at the Oxford Martin School earlier this week. I wasn't able to make it in person, but the talk, and the Q and A that followed it, can be seen here. After watching it, I'm more than ever convinced that we're witnessing a historic paradigm shift in the ways we produce, distribute and use energy, a shift away from carbon-emitting energy and towards a low-carbon energy future. Anyone who doesn't engage positively with this change will be swept away by it.

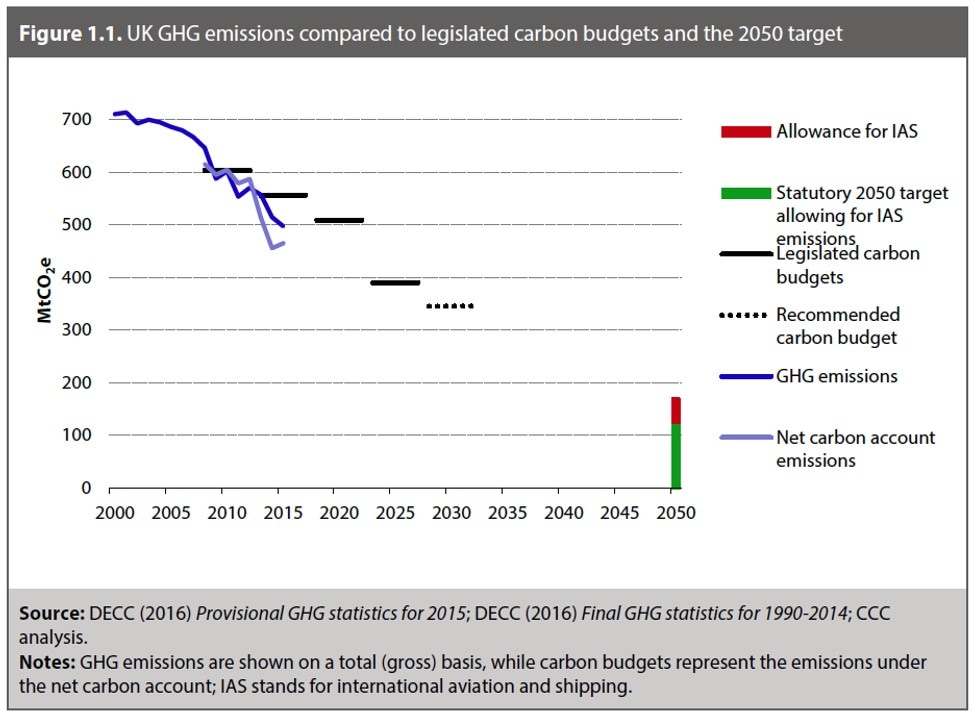

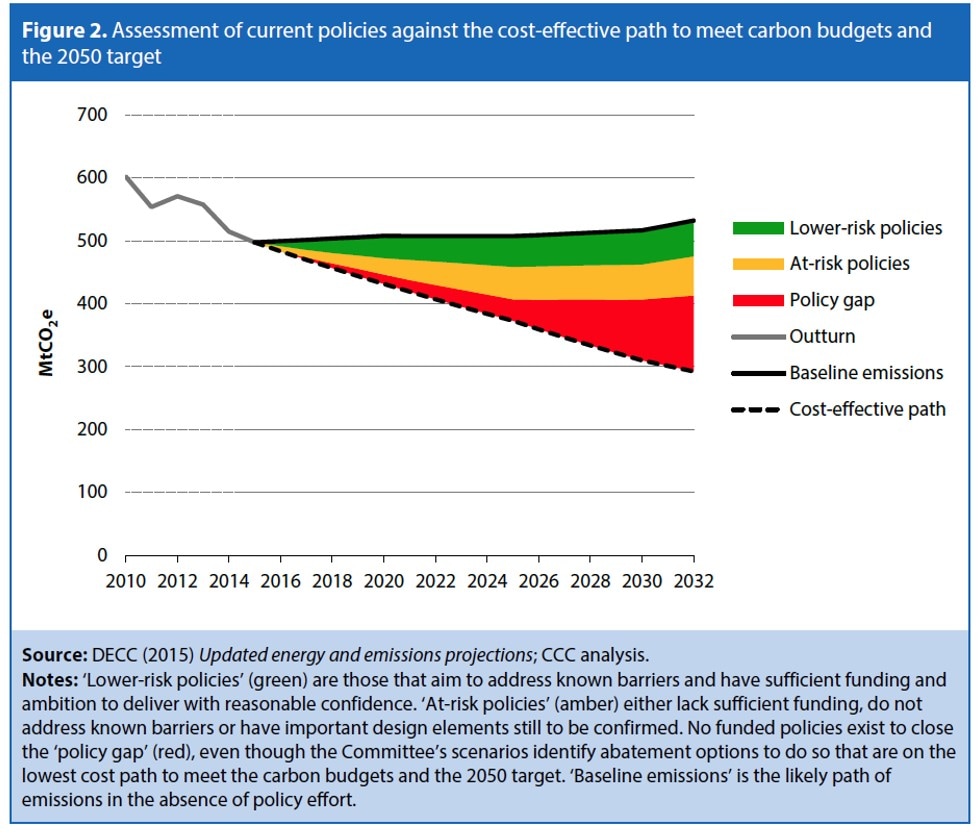

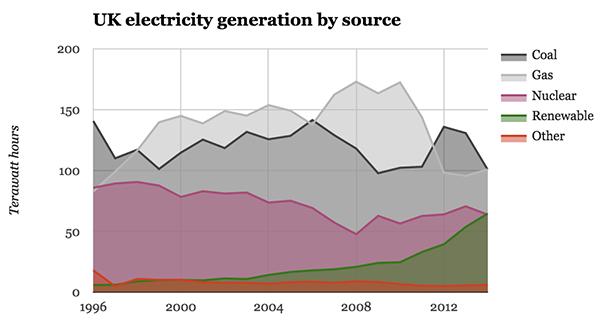

According to the UK Committee on Climate Change, the UK Government has a policy gap on meeting its climate change obligations. My interpretation of the following two charts from its 2016 report is that the UK Government has 'picked the low-hanging fruit' by providing a good rate of progress in shifting towards renewable energy generation, but has not yet made difficult but necessary decisions on other aspects of our systems that generate carbon emissions. One of these that is particularly difficult but also particularly important is the embedded carbon emissions in goods and services imported from other countries. This is one of the ways we currently "export" our carbon emissions, essentially by getting other countries to emit on our behalf, so that it looks like they are the emitters, for many of the goods we consume in the UK.

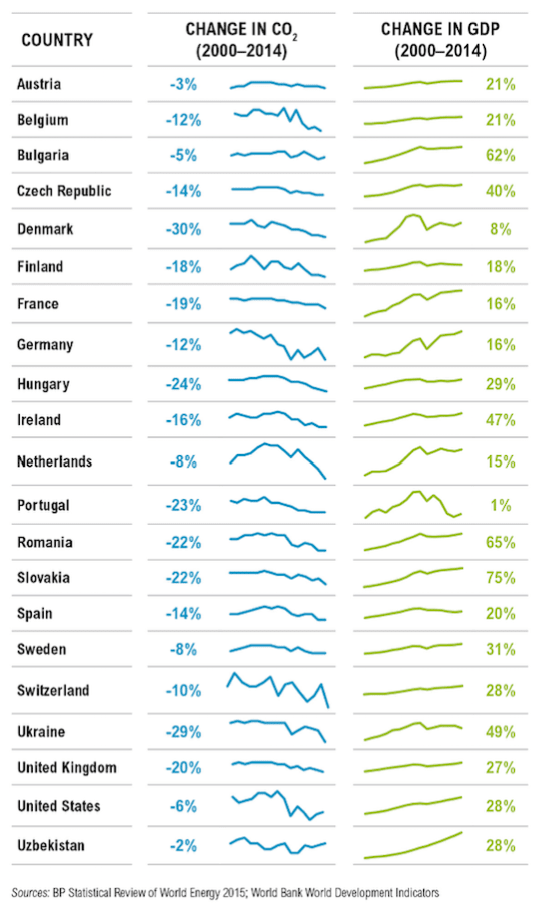

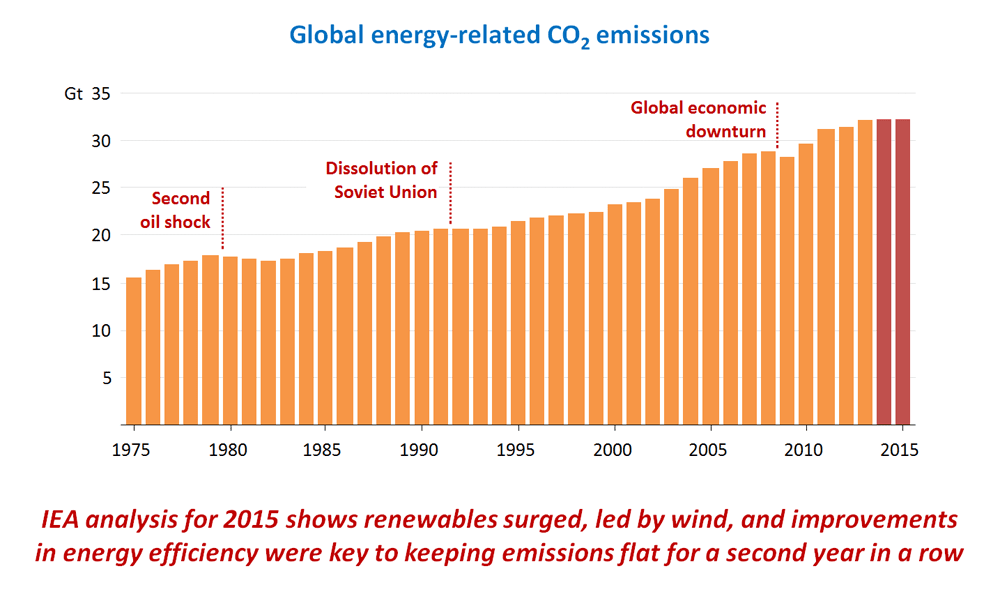

Just to signpost, some of the key elements of this debate are at: http://www.carbonbrief.org/the-35-countries-cutting-the-link-between-economic-growth-and-emissions and: https://steadystatemanchester.net/2016/04/15/new-evidence-on-decoupling-carbon-emissions-from-gdp-growth-what-does-it-mean/ Much of the debate was triggered by the following infographic from Carbon Brief. The core of the debate is about the accuracy of the data and the extent to which it might suggest causality, or just correlation without causality (instead). Also, more detailed analysis of the data might suggest that there are other factors involved rather than a simplistic, direct link between carbon emissions and the carbon-intensity of production and consumption patterns in the listed countries. For example some offshoring of carbon-emitting production processes would tend to reduce the territorial carbon emissions of the listed countries but increase the carbon emissions of other countries not listed without affecting GDP per se. This offshoring might represent a significant part of the explanation of the headline trends, throwing doubt on the headline suggestion that carbon emissions are decoupling from GDP. To allow for these effects, it would be good to see the global total GDP trends and carbon emission trends, rather than just data on each of these for a few selected countries. There is some global data reported in the Guardian at:

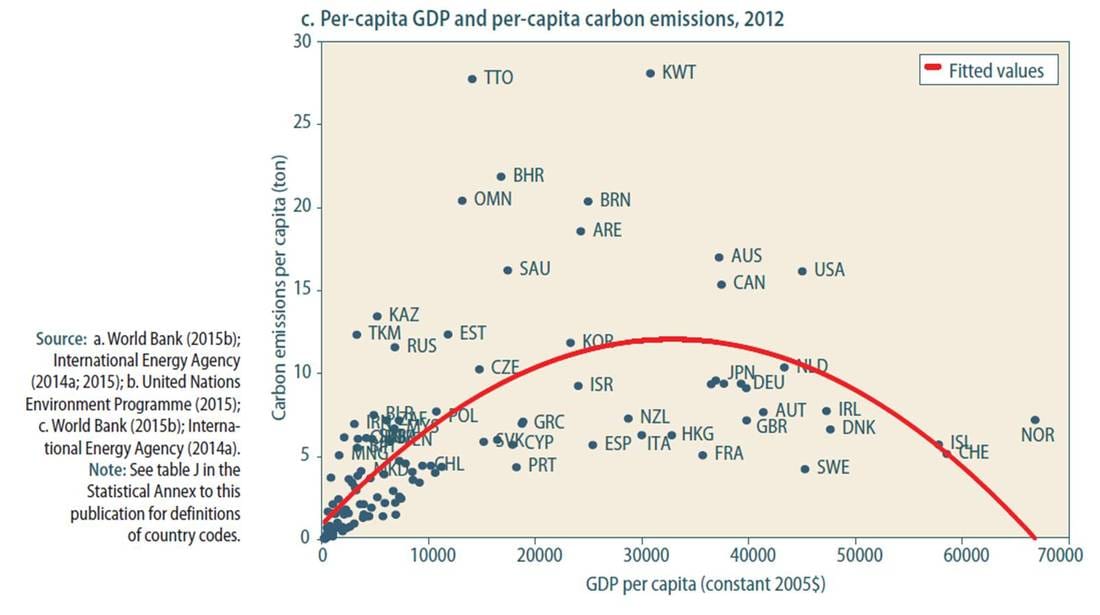

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/apr/14/is-it-possible-to-reduce-co2-emissions-and-grow-the-global-economy and this suggests that one factor is that Chinese energy production from coal has recently been growing less rapidly than in the past, and so there is some hope for a green revolution in China. But it appears to be quite difficult to get a comprehensive picture of all the various factors linking carbon and GDP and the cause-and-effect relationships between all of them. Perhaps, also, longer-term data needs to be collected and analysed before more confidence can be built in any conclusions reached. A starting point for this might be an IEA article at: https://www.iea.org/newsroom/news/2016/march/decoupling-of-global-emissions-and-economic-growth-confirmed.html and, in particular, the following highlights, albeit discussing only the most recent two year period when there appears to have been global GDP growth but without much increase in global carbon emissions: "Global emissions of carbon dioxide stood at 32.1 billion tonnes in 2015, having remained essentially flat since 2013. ... In parallel, the global economy continued to grow by more than 3%, offering further evidence that the link between economic growth and emissions growth is weakening." Of course, a trend over two years is not very conclusive in this complex area, which is why I make the comment above about the need to look at trends over much longer timeframes, perhaps even decades. The diagram above is from "World Economic Situation and Prospects 2016" published by the UN. On the face of it, this provides some hope about the state of decoupling of carbon emissions from per capita GDP. If sufficient decoupling can be achieved, then an amount of aggregate global GDP growth could be achieved while keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

However, there is one aspect of this which is of some concern. There is a nagging question on my mind. What if the reduction in per capita carbon emissions in high-GDP countries is largely achieved by 'exporting' carbon emissions, ie by consuming products and services imported from parts of the world which have much higher per capita carbon emissions? If this was the case, then, all other things being equal, it wouldn't be possible for all countries to be moved, over the years and decades, from bottom left of the diagram to the bottom right. This is because there wouldn't be any countries remaining in the bottom left to "export" carbon emissions to. I'd be happy if anyone can point me in the direction of evidence that can put my mind at rest on this point. And perhaps one of the most important questions following on from that is: "what would be the distribution of countries on the above curve at a sustainable equilibrium, and would that equilibrium be consistent with operating within sustainable and safe planetary limits (as per the Oxfam sustainability "doughnut" model)?" This diagram is part of the reason I'm happy to use an Electric Vehicle in the UK - The mix of energy generation which provides the electricity I charge it with is moving rapidly from fossil fuels to renewables, from high carbon emmitting sources to low or zero emitting sources. Also, I have solar panels on my house, so some of the time I'm using locally generated electricity to charge the car rather than drawing it from the grid.

|

AuthorThe Planetary CFO - working towards a sustainable World Balance Sheet. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|