|

Linked here, this podcast is an excellent summary of the interplay between climate change and UK politics.

0 Comments

Response to Mark Carney’s 4th Reith Lecture 2020 - From Climate Crisis to Real Prosperity28/12/2020 I’ve just been listening to this fascinating Reith Lecture by Mark Carney on the BBC.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000qkms He quite correctly identified the main features of the Climate Crisis and some of the ways many people in the worlds of finance and economics are trying to solve this presenting problem, and even to go further to build a sustainable future beyond just stabilising the climate. He is to be commended for such a salient and well-constructed series of talks, of which this one was the fourth and final one. He seems to place a lot of confidence in the ability of market mechanisms, operating alongside government policies and regulatory legislation, to provide the shift in investment required to rebalance human activities and reflect changing citizen values on the planet and sustainability. In my view, if I can be a "critical reviewer" for a moment, he gave only a partial response to the question by Tanya Steel (WWF) – about 42 minutes into the transmission – regarding the lack of valuations being placed on standing rainforests (as opposed to felled forests for land use change into agriculture). Although he mentioned Natural Capital, he expressed some concerns about using Natural Capital approaches to put a value on nature. His main concern, which has been expressed by others (including the famous environmentalist George Monbiot), is that putting a value on nature could make it easier (and more attractive) for businesses or individuals to make profits by exploiting those natural assets, in particular by converting them from capital assets into produced goods (eg cutting down trees to make wood and changing the land from forest use into more profitable agricultural use. This is a well-worn concern about Natural Capital but it can be addressed. The key thing to realise is that, in most forests, the fact that they are not valued at all as a standing capital asset makes it much easier for them to be exploited for profit than if they had a standing forest value as a capital asset. This is because the cost of the raw material is currently essentially zero and no economic damage is recognised when the trees are felled. Placing a value on the standing forest as a capital asset (Natural Capital) would make it clear that felling the trees in an unsustainable way would be destroying value, by reducing the value of that capital asset without a larger compensating value creation from that activity. The main solution is to emphasise the necessary change of priority from a “flow” model of the economy (as typified by GDP) to a “stock” model, with managing national and global Balance Sheets being more important for a sustainable future than just managing the annual flows (equivalent to a profit and loss account). Stock Flow Consistent (“SFC”) economic modelling has been around for several years, and it was a missed opportunity for Mark Carney not to mention this in his lecture. The SFC approach follows the premise that it is important to manage balance sheets as well as income and expenditure if you want your enterprise to have a long-term future. If that enterprise is an entire country (or the whole world) then we have for too long focussed almost entirely on the income and expenditure (eg GDP) and neglected the national and global balance sheets (incorporating Natural Capital). SFC modelling is, in fact, one of the most obvious things to explore as part of current moves to implement Natural Capital in National Balance Sheets (in National Systems of Accounts), and ultimately we should be maintaining and enhancing World Balance Sheets over time, including the whole of the Natural Capital of the Earth, as this is what the continued thriving of our species (and many others) depends on. For more about this concept, see WorldBalanceSheet.com Steady State Economics might not be the best answer to current and future sustainability challenges. It might not even be sufficient as a solution, in its current form, as advocated by CASSE (The Centre for Advancement of Steady State Economics).

It might, however, be a useful stepping stone to better solutions we can’t yet know about, let alone express in economic terms. Some of the work of Brian Czech, Director of CASSE, and other authors in “Best of the Daly News” (ie Czech, 2020) is examined further below and in my forthcoming book, due to be published in 2021. And SSE might be a whole lot better than the current way economies are managed (or left to markets) in most parts of the world today. However, it's worth setting some wider context first, which will help to explain why this, and other new forms of economic thinking, are a necessary field of thought and practice to address our current predicament. The Bottleneck humanity hopes to pass through “The Precipice” by Toby Ord (ie Ord, 2020) resonates with my own perspectives on the long-term development of humanity and the risks it currently faces. Ord points out that humanity is at a critical crossroads, where its power has outstripped its wisdom, resulting in several serious existential risks (including unsustainability of our impacts on nature, rogue AI (Artificial Intelligence), engineered biological agents and conflicts that might, potentially, involve nuclear weapons). The finite planetary limits of the biosphere that supports us are like a bottle containing a model ship in the classic “ship in a bottle”. Our population and civilisation are like the ship. The human ecological footprint has been growing as we have developed (the ship has been growing in size and complexity inside the bottle). But we are realising that the finite bounds of the biosphere, and the damage caused by our overshooting sustainable thresholds, is reducing the size of the biosphere and its capacity to support us (the neck of the bottle has been narrowing, as a result of our actions) and the rate of that depletion in biospherical capacity is accelerating. We want humanity to progress further, because our future potential is immense if we can more effectively harness the energy from the sun (the only input from outside the bottle) and if we can access materials from outside the earth system, for example by mining materials on the moon, from asteroids or find even more distant exploitable resources. After all, the universe outside the bottle is potentially infinite in materials, energy and evolutionary progress for living beings. Our challenge is to pass through the neck of the bottle, and to pull what we can of the ship, through with us, without destroying the bottle that is humanity’s birthplace. It becomes obvious there are two main options for doing this, which are not mutually exclusive. Firstly, we can modify our impacts on the natural biosphere, to reduce (and eventually reverse) the rate of degradation of the biosphere’s capacity to support us (slow down, and then reverse, the rate at which the neck of the bottle is shrinking). Secondly, we can alter our civilisation and the way it draws resources from the biosphere and uses them, for example adopting circular systems of material and energy flow, such as those advocated in circular economy, or even implementing something along the lines of a steady state economy, a GDP-growth-agnostic economy or something similar (remodel the ship so it will more easily pass through the neck). If we can do these things, a bright future awaits and the innumerable future generations of humanity will thank us for our efforts. If we fail, however, our failure will go down in history as the biggest failure of any known life reaching a state of advanced intelligence and civilisation. We should use the sense of responsibility this imparts as a spur to action. The bottleneck analogy is used also, extensively, in White and Hagens (2020) “The Bottlenecks of the 21st Century”. I think Daniel Yergin's "The Commanding Heights" is an excellent and highly relevant book, published in 1998 but still highly relevant today. I find myself dipping into it again and again, as it tracks the ebb and flow of the balances (and imbalances) in many nations and globally between 'the market' and 'the state' or (occasionally) global governance mechanisms. Although he seems (mostly) to fall on the side of supporting market approaches, at the end of the book he hints at the possibility of a resurgence of 'the state' and its role as regulator of things like environmental protection and climate change where markets fail or generate damage and harm.

The following is from page 390: “Yet if the market is seen to fail on either of those two grounds - results and restraint - if its benefits are regarded as exclusive rather than as inclusive, if it is seen to nurture the abuse of private power or the specter of raw greed, then surely there will be a backlash - a return to greater state intervention, management, and control. The state would again step forward to expand its role as protector of the citizenry against the power of private interests, whether exercised through monopoly, wanton behaviour, fraud and deception, or exploitation and direct harm." Was Yergin hedging his bets, or expressing some real concerns and fears that markets, insufficiently fettered, would be likely to wreak havoc with the planetary biosphere and climate, throwing us well beyond sustainability thresholds and requiring increasingly drastic national and international government and governance actions? Tietenberg (2018) provides similar conclusions: “In summary, the record compiled by our economic and political institutions has been mixed. It seems clear that simple ideological prescriptions such as “leave it to the market” or “let the government handle it” simply do not bear up under a close scrutiny of the record. The relationship between the economic and political sectors has to be one of selective engagement, complemented in some areas by selective disengagement. Each problem has to be treated on a case-by-case basis. As we have seen in our examination of a variety of environmental and natural resource problems, the efficiency and sustainability criteria allow such distinctions to be drawn, and those distinctions can serve as a basis for policy reform … Our examination of the evidence suggests that the notion that all of the world’s people are automatically benefited by economic growth is naïve. Economic growth has demonstrably benefited some citizens, but that outcome is certainly not inevitable for all people in all settings.” The "commanding heights" of the economy (nationally and globally) continue to be a vital piece of context for the challenge of transitioning (or 'transcending') to sustainability, and our money systems play a key part in that. Maintenance and reform of money systems are a legitimate role for the state. These issues transcend party politics. Indeed, I think the vision of achieving global sustainability and social justice is often damaged when it becomes co-opted by political movements, as these often result in polarisation of debates, and unnecessary conflicts. Critique of willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-receive methods for valuing natural capital12/11/2020 One valid criticism of economic valuation approaches is where they are based on willingness-to-pay (to acquire the asset not currently owned) or willingness-to-accept (to accept compensation for the loss of the asset currently owned). In many cases, and especially in relation to valuing nature, there is likely to be an element of hypothetical bias in people’s answers to surveys of their willingness-to-pay or willingness-to-accept preferences.

Hypothetical bias can enter the picture because the respondent is being confronted by a contrived, rather than an actual, set of choices. Since he or she will not actually have to pay the estimated value, and has potentially very little understanding of the significance of the hypothetical scenario underlying the question, the respondent may treat the survey casually, providing ill-considered answers. A particular case of this is where the respondent is being asked about the value of a natural asset (eg natural capital comprising part of the global commons), when it is currently valued at zero and the respondent (via the global industrial supply chains) is currently not paying anything for the use (or abuse and exploitation) of that asset. These sorts of valuation methods can also be undermined by the personal circumstances of the respondent. A respondent with very small amounts of financial resources (eg income) is likely to give much smaller willingness-to-pay answers than one with much larger financial resources. Let me paint a hypothetical scenario to illustrate this. For those of you who have heard of the Biosphere 2 experiment in the 1990s, imagine a re-run of that 2-year experiment. For those unfamiliar with it, Biosphere 2 was a project where 7 volunteers lived inside a closed set of connecting bio-domes containing air, water, soil, plants etc with no inputs or outputs (wastes) allowed to enter or leave the domes, except for the sunlight falling on them and the energy ‘leakage’ out through the glass walls at night. Everything was recycled that possibly could be. In the imaginary re-run, which I’ll call Biosphere 3, because of the strict limits on availability of such materials, suppose that each inhabitant had a daily budget of financial resource, and each of the main materials required for survival was made exclusive to each “consumer” (eg with breathable air provided via breathing apparatus and personal cylinders, and exhaled air collected in similar cylinders for recycling, water provided in personalised bottles, food in personalised containers) But suppose further that this was all provided as a public good for the first six months, on a strictly need-to-consume-for-survival basis. Suppose also that some inhabitants had financial resources very different from others – say, some had $100 per day while others had $100,000 per day. In this scenario, what would willingness-to-pay or willingness-to-receive questioning and valuation methods reveal about the values of the various survival essentials? I would guess that the answers would be very different between participants with different financial resources, and they would also be very different with passage of time. On day one, probably everyone would be willing to pay almost all, if not actually 100%, of their ‘budget’ for breathable air (even if they don’t actually have to pay for it), on the basis that none of them could survive the day without breathable air, whereas everyone could survive without water or food for one day. The trouble with that is that it gives a value for breathable air of $100 for some respondents, $100,000 for other respondents. As long as this doesn’t affect the actual amounts of air, water and food provided (because they are being provided as a public good, not as a market-traded exchange) there is no problem with continuing provision. The situation would get more complicated some days later, because after some days without water, survival would become a matter of securing water as well as air, and after an important threshold of deprival, no amount of air (or money) would compensate for lack of water, without which death would follow. Therefore, everyone would be prepared to pay something for some water, even if all the rest of their budget would be allocated to breathable air in their willingness-to-pay answers. So, perhaps their willingness-to-pay valuations would represent 90% of their “budget” for air and 10% for water each day, in order to survive until the next day. Some time after that point, edible food would have to be part of their answers, to avoid theoretical death, on the basis that no amount of money, air and water can stop someone dying if they don’t have food. So perhaps their valuations of willingness-to-pay would represent 90% of the budget allocated to air, 7% to water and 3% to food each day, in order to survive to the next day. And so on. Perhaps this situation and the associated willingness-to-pay values would reach some form of stable equilibrium after, say, six months. It can easily be seen that the “values” of each of the necessities, as measured by willingness-to-pay, would vary considerably between participants, and would vary considerably over time during those first six months. Now consider the scenario that the actual costs of providing all those necessities each and every day in Biosphere 3 was a lot higher than any of the personal financial resources of the ‘poorest’ of the individual participants, but not beyond the financial resources of the ‘richest’ participants. Assume, for example, that the cost of breathable air was $50,000 per day per person, water was $30,000 and food was $10,000. Further, assume that the “provider” after the first six months changed, and was then a computer or Artificial Intelligence operating on market exchange principles (a complete contrast from providing essentials as a public good), and was unwilling (or unable) to compromise and incur a ‘loss’ on provision (eg the provider was not going to accept a lower price than the actual cost of provision). It will be clear that this is a very different state of affairs compared with the first six months of public good service provision. The willingness-to-pay answers for the poorest participants under this new model for ‘traded’ provision would now be, in fact, an irrelevant and gross under-estimate of the value of the provision, for any answers they give, even if they answer 100% of their personal budget (ie $100 per day) as the willingness-to-pay value for any one of the essentials. They simply won’t survive day one, because they don’t have sufficient financial resources to pay for the true cost of the provision of the essentials for life. Their survival during the first six months was dependant on the provider subsidising the true ‘cost of living’ (ie incurring the cost of the public goods themselves and not passing them on to the consumer). At least some of the “richer” participants might well survive the new regime for provision, but even though some of them might be able to cover the average actual costs of provision, they might not all survive the whole 2 years. For example, if there is a bidding war, and if the Artificial Intelligence has profit maximisation as its aim, its optimum market strategy might be to use its monopoly power to manipulate prices to extract the maximum revenue, even if this means only very few participants surviving to the very end of the 2 years. This might seem a very extreme scenario, contrived in order to challenge the validity and accuracy of willingness-to-pay or willingness-to-receive valuation methods. However, if you consider for a moment the overall insights derived from Kenneth Boulding’s “Spaceship Earth” conceptual writings, it doesn’t take a huge leap of the imagination to see how the whole of the Earth can be thought of as a larger version of Biosphere 3. In fact, the reason the 1990’s dome experiment was called Biosphere 2 was because it’s designers considered the Earth to be “Biosphere 1”. So, Biosphere 1 (the current Earth we live on) has some similarities with Biosphere 3. The Earth is a finite, closed system, except for the sunlight falling on it (and the solar energy escaping through the atmosphere into space). The main differences between the Earth (Biosphere 1) and my hypothetical, imaginary Biosphere 3 are matters of scale, the key ones being the overall size of the Earth and its biological and chemical systems, and the size of the global human population. With this perspective in mind, my “Biosphere 3” thought experiment can be seen to challenge the willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-receive valuation methods used in Biosphere 1 (the Earth we live in). The Biosphere 3 scenario highlights the downsides of a marginalist approach to valuation. Willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-receive approaches are difficult to apply without the respondents falling into a marginalist perspective. That is, they are very likely (even if subconsciously) to consider a price or value in a way that is heavily influenced by their current circumstances and by the existing state (and prices / values) of the objects in the existing systems of supply (whether market-based or public goods provision). Many of these existing prices / values are effectively zero or heavily subsidised in current global supply chains, so this is likely to give a very strong bias towards very low valuations resulting from these methods of valuation. I've just published the World Balance Sheet 2018 here. This is an illustrative example intended to spark debate and ideas, rather than a finished or perfect object. Very few people have even attempted to create such a balance sheet. I've built on the work of one of those who has - Harald Deutsch - amending it and enhancing it through a lens of sustainability, for example by adding in natural capital. What my world balance sheet shows is that there is a significant "asset stewardship shortfall" of about USD 600 trillion. This arises mostly from degradation, and drawing down, of natural capital to meet humanity's aggregate consumption. I think the overall message is clear - we need to repair, enhance and maintain adequate natural capital to reduce the asset stewardship shortfall and eventually restore the balance in the world balance sheet.

The consultation is a first step in the right direction. It sets out the proposed new legislation as a means to make supply chains more sustainable, by requiring large companies to undertake due diligence on their (global) supply chains regarding the sustainability of the harvesting of commodities (eg timber) from forests. However, inevitably this will initially fall short of being optimum for sustainability. This is because it is currently expressed in a form that represents a type of "weak sustainability".

Thresholds (for the scope of the legislation) should be set to cover a specific proportion of the amount of forest risk commodities involved in the UK economy. Those thresholds and proportions should be reviewed and revised every few years, and progressively tightened until the point of diminishing ecological returns. I believe in "strong sustainability" and would recommend moving as swiftly as possible from the initial position to a position where the sum total of the world's natural capital is maintained and improved to a point of being optimal. This will go beyond many nations' existing laws, and will need to be backed up by new international laws. I participated in an A4S webinar yesterday on "Measure What Matters: Capitals Accounting". It was an excellent opportunity to engage with a network of CFOs on some of the big issues relevant to accounting and sustainability.

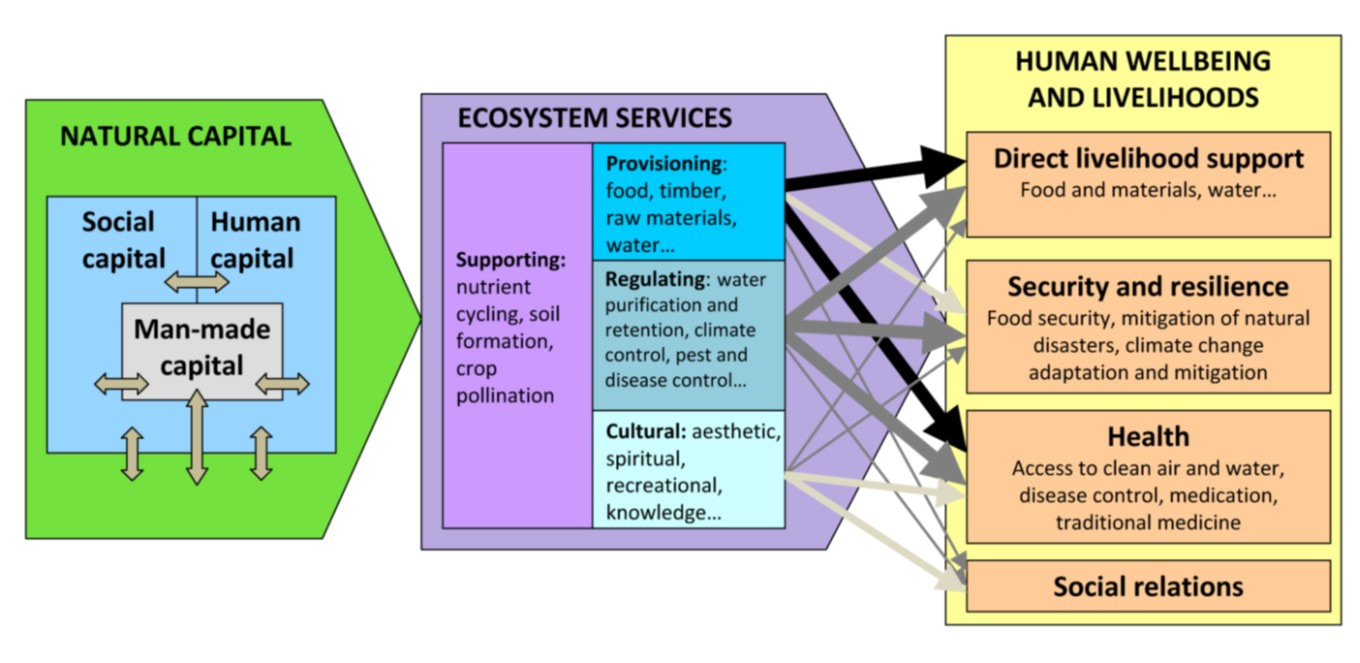

One of the discussion points was about substitutability of capitals, and, in particular, whether Natural Capital should be substitutable for other forms of capital. For context, the diagram above is from TEEB (2018) "Measuring what matters in agricultural food systems". The diagram was adapted by the authors of TEEB (2018) from an original source, which was the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 Synthesis Report. The general view from the webinar leaders/panelists, including a representative from TEEB, was that Natural Capital should not be substitutable for other types of capital. Full stop. No ifs, no buts. Natural Capital should be maintained (even enhanced) and not converted into other types of capital (for example, produced capital or financial capital). This draws on (and is almost a definition of) a concept of Strong Sustainability, rather than Weak Sustainability. Strong Sustainability is a concept I support, as a suitable response to the mounting evidence that generations of people have not just neglected but caused massive amounts of destruction and degradation to Natural Capital around the world, pushing us far into ecological overshoot, as highlighted very graphically by Earth Overshoot Day. It also means that individual businesses, as well as all other types of organisation, when assessing their impacts and dependencies, should carefully and separately identify the distinctions between the goods and services which Natural Capital provides as inputs to their business models, as distinct from the Natural Capital which provides them. (This is something that many organisations have been woefully poor at doing throughout modern history). They must not degrade or deplete the Natural Capital, for example by causing goods and services drawn from Natural Capital sources to exceed that which can sustainably be produced by that Natural Capital in perpetuity. Also, they must not allow their business processes to cause more carbon emissions, other waste or damage than can be sustainably accommodated by the Natural Capital in perpetuity. At an aggregate global level, the development of a World Balance Sheet will help us to assess whether the combined activities and impacts of all organisations, whether businesses or not, are complying with these requirements. The whole of the world's Natural Capital will be a key component of the World Balance Sheet. See more about the World Balance Sheet concept in my previous blog posts and at WorldBalanceSheet.com. On that site, I list my recent books, published this year, which go into more details about the emergence of the World Balance Sheet concept. These are very early days for the World Balance Sheet, but my hope is that we will rapidly reach the point where it will tell us whether enough people are practising Strong Sustainability to make a real difference in the transition to a just and sustainable future for the whole global population, today and in perpetuity. Land

In this article, I will argue that land, one of the most important but scarce (ie finite) assets on the planet, is undervalued and over-exploited. This is one of the key reasons we face continuing degradation of the biosphere, damaging the long-term sustainability of ecological systems and therefore threatening our own ability to survive and thrive in perpetuity. But I will also point out that some of the key building blocks for addressing this set of challenges are already in place. All we need to do is link up the disciplines of sustainability, ecology, accountancy and economics in a quest to place proper values on the assets and obligations associated with land ownership. But let’s start by looking at definitions. There is a high degree of consensus, in language dictionaries, on the definition of land, as shown by the following two examples: “The surface of the earth that is not covered by water” (Cambridge English Dictionary) “The part of the earth’s surface that is not covered by water” (Oxford English Dictionary) Although quite simple, these definitions are helpful in some ways, but unhelpful in others. Defining land by what it is not (not covered by water) helps to some extent with a ‘first approximation’ when assessing a part of the earth’s surface. We can ask “is it covered by water?” If the answer is “no” then it is, by definition, land. On the other hand, how far does the “land” extend below the surface (down through the soil and rock) or, for that matter, above the surface (up through the atmosphere and into space)? And does it include the living organisms that inhabit the land, the soil, the non-oceanic water and the air? Wikipedia gives us a rather more descriptive (if more wordy) definition, based on economics, and some inkling of key challenges surrounding ownership: “In economics, land comprises all naturally occurring resources as well as geographic land. Examples include particular geographical locations, mineral deposits, forests, fish stocks, atmospheric quality, geostationary orbits, and portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Supply of these resources is fixed ... Because no man created the land, it does not have a definite original proprietor, owner or user. “No man made the land. It is the original inheritance of the whole species.” (John Stuart Mill) As a consequence, conflicting claims on geographic locations and mineral deposits have historically led to disputes over their economic rent and contributed to many civil wars and revolutions.” There follows a quite typical current “economic” view on land and how it is treated in most economic calculations. Excerpts from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/land.asp -------- excerpts start ------------------------- Land By JAMES CHEN Updated Jun 4, 2020 What Is Land? Land, in the business sense, can refer to real estate or property, minus buildings, and equipment, which is designated by fixed spatial boundaries. Land ownership might offer the titleholder the right to any natural resources that exist within the boundaries of their land. Traditional economics says that land is a factor of production, along with capital and labor … Land qualifies as a fixed asset instead of a current asset. ... More Ways to Understand Land In Terms of Production The basic concept of land is that it is a specific piece of earth, a property with clearly delineated boundaries, that has an owner. You can view the concept of land in different ways, depending on its context, and the circumstances under which it's being analyzed. In Economics Legally and economically, a piece of land is a factor in some form of production, and although the land is not consumed during this production, no other production - food, for example - would be possible without it. Therefore, we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production. [I’ll provide a criticism of this interpretation below] Despite the fact that people can always change the land use to be less or more profitable, we cannot increase its supply. Characteristics of Land and Land Ownership Land as a Natural Asset Land can include anything that's on the ground, which means that buildings, trees, and water are a part of land as an asset. The term land encompasses all physical elements, bestowed by nature, to a specific area or piece of property - the environment, fields, forests, minerals, climate, animals, and bodies or sources of water. A landowner may be entitled to a wealth of natural resources on their property - including plants, human and animal life, soil, minerals, geographical location, electromagnetic features, and geophysical occurrences. Because natural gas and oil in the United States are being depleted, the land that contains these resources is of great value. In many cases, drilling and oil companies pay landowners substantial sums of money for the right to use their land to access such natural resources, particularly if the land is rich in a specific resource. … Air and space rights - both above and below a property - also are included in the term land. However, the right to use the air and space above land may be subject to height limitations dictated by local ordinances, as well as state and federal laws. … Land's main economic benefit is its scarcity. The associated risks of developing land can stem from taxation, regulatory usage restrictions … and even natural disasters. ------- excerpts end ---------- I would take strong exception to Chen’s statement that “we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production”. This treatment of land would be to grossly abuse it and under-value it, both in pure economic terms but also in terms of encouraging accelerating environmental degradation. In direct contrast to Chen’s description of land’s role in production, I would argue that land needs to be restored and maintained in a sustainable state that not only supports any economic production that relies upon it, but also so that the land performs, in perpetuity, its proper role as part of earth’s living biosphere. Accounting Guidance The International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”), and the International Accounting Standards (“IAS”) set the international frameworks guiding all accountants around the world in what is deemed to be acceptable ways of accounting for everything that appears in a balance sheet or a profit and loss statement. An example is the way assets are valued and reported. There are a number of accepted ways of attributing, or calculating, a value for an asset, including “land”. In accounting guidance, land is included in “property, plant and equipment”, being a particular type of “property”. Excerpt from IAS 16 ---------------------------- Property, plant and equipment are tangible items that: (a) are held for use in the production or supply of goods or services, for rental to others, or for administrative purposes; and (b) are expected to be used during more than one period. The cost of an item of property, plant and equipment shall be recognised as an asset if, and only if: (a) it is probable that future economic benefits associated with the item will flow to the entity; and (b) the cost of the item can be measured reliably. If the cost of land includes the costs of site dismantlement, removal and restoration, that portion of the land asset is depreciated over the period of benefits obtained by incurring those costs. Excerpts end ---------------------- From the excerpts above, we can build on what I have said about the obligation to maintain land to fulfil its role as part of a sustainable living biosphere. All that is required is to establish, and enforce, the principle of holding owners of land to account for maintaining the land sustainably. This needs to be backed up by national and international governance mechanisms (eg national and international laws and environmental regulations). When those governance measures are in place, then the asset value of any piece of land an owner wants to hold will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner. If the land’s current state is a long way below that which would be considered biospherically sustainable, then the value of the land might even be negative, because although the owner has an asset that will produce some positive economic value, for example from agricultural produce generated from it, there could exist a large obligation (liability) to set against that, representing the amount the current owner needs to spend to restore the land to a biospherically sustainable state. If the liability is larger than the value of the economic productivity of the land, then the land (asset) net value will be negative. It follows that the market price of any piece of land an owner wants to sell will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner and also the same obligation on the new owner. It is probably quite clear that, in the paragraphs above, I’ve based my arguments on a definition of strong sustainability when using the terms “sustainable” and “sustainability” etc. Can cryptocurrencies ever be recorded in a World Balance Sheet? Let's look at some of the key features of Bitcoin, as an example of a cryptocurrency:

According to wikipedia:

Although Bitcoin is (in theory) decentralised, wikipedia also says: "As of 2013 just six mining pools controlled 75% of overall bitcoin hashing power.[134] In 2014 mining pool Ghash.io obtained 51% hashing power which raised significant controversies about the safety of the network. The pool has voluntarily capped their hashing power at 39.99% and requested other pools to act responsibly for the benefit of the whole network.[135] c. 2017 over 70% of the hashing power and 90% of transactions were operating from China." Bitcoin isn't backed by any assets in the real world. Therefore, even though it is said that their design and implementation will result in a maximum of 21 million Bitcoins ever being created, they are only ever going to have a value determined by owners' and users' perceptions of value, not any related underlying value of real assets in the real world. This makes them even more ethereal than any national currency anywhere in the world, which at least has the benefit of some asset backing (albeit on a fractional banking ratio) underwritten by a real-world institution such as a national central bank. The risks associated with recognising the value of Bitcoins should be fairly obvious from this. There can be no confidence that their supposed value will continue to exist, and at any point they might become valueless. There is no authoritative body that can be called upon to take any action to stabilise the value of Bitcoins. Indeed, there is a risk that any such putative body that purported to be able to do so could be a fictitious body, or a legitimate body acting fraudulently or negligently. Exchanging any real-world national currency, or other assets, for Bitcoins represents, therefore, nothing more than pure speculation on the future value of an imaginary asset. For this reason alone "I'm out!" and I will not be recommending inclusion of any cryptocurrencies in the World Balance Sheet. Yesterday, I participated in this online meeting and discussion. There were talks by Ben Caldecott and Anna Olerinyova, followed by Q and A. I found this a fascinating discussion.

There is one exchange in the chat that I’d like to follow up on. At one point, another participant and I had a brief exchange about Steady State Economy, and they signposted a paper: “Another reason why a steady-state economy will not be a capitalist economy”, by Ted Trainer [University of New South Wales, Australia] http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue76/Trainer76.pdf The central tenet of Trainer’s paper was to say that Herman Daly had said that capitalism could not exist in a steady state economy unless there was considerable decoupling of economic growth from material throughput. The following is a quote from the paper: “... Daly’s case that a steady-state economy can remain capitalist depends entirely on the assumption that there is considerable scope for technical advance to enable productivity gains and decoupling, and for this to continue indefinitely” Trainer seems to be arguing that steady state economics is not enough, and supports an alternative called The Simpler Way, and that might be why he has taken quite a negative view on the supposed inconsistencies between Daly’s steady state economics and capitalism:. From Trainer’s paper (I have emboldened the most relevant text): “It should be evident from the above discussion that it is not sufficient merely to take a steady-state economy as the goal. When the seriousness of the limits to growth is understood, as the above multiples make clear, it is obvious that a sustainable and just society must have embraced large scale de-growth. That is, it must be based on per capita resource use rates that are a small fraction of those typical of rich countries today; it must in other words be some kind of Simpler Way. (For the detail see TSW: The Alternative.)” I’ve found a different source (Wikipedia) that suggests that this is perhaps a rather extreme interpretation of what Daly actually believes (or, at least, believed in 1980) – in which I’ve emboldened the most relevant text: “Fully aware of the massive growth dynamics of capitalism, Herman Daly on his part poses the rhetorical question whether his concept of a steady-state economy is essentially capitalistic or socialistic. He provides the following answer (written in 1980):’The growth versus steady-state debate really cuts across the old left-right rift, and we should resist any attempt to identify either growth or steady-state with either left or right, for two reasons. First, it will impose a logical distortion on the issue. Second, it will obscure the emergence of a third way, which might form a future synthesis of socialism and capitalism into a steady-state economy and eventually into a fully just and sustainable society’. Daly concludes by inviting all (most) people — both liberal supporters of, and radical critics of, capitalism — to join him in his effort to develop a steady-state economy.” Thought this might be useful as a counter, from Herman Daly himself, to what Trainer claims about him. The Planetary CFO has published a first book, titled "Peak XXXX: Infinite Possibilities on a Finite Planet". This is a high-altitude fly-by of most of the key sustainability challenges and opportunities on the way to creating a just and sustainable future for everyone. From the imaginary overview from the stratosphere, I helicopter down into a few of the most exciting topics (and some technical ones, I have to warn you) and string them together with sustainability glue. I hope you enjoy it, and can get something from it. It can be bought on Amazon at the following link: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Peak-XXXX-Infinite-Possibilities-Version/dp/B089TV3GBW/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=peak+xxxx&qid=1595331694&s=books&sr=1-1 Pairs of air jets could do the trick - for more info see my article on my "Ideas in a Nutshell" page.

The article here about research from the Roosevelt Institute suggests that Universal Basic Income ("UBI"), if implemented in the USA, would have a positive impact of about 2.5 trillion dollars on the US economy.

However, a rider to the argument in the article is that this effect is predicted if the measure is funded by increasing the nation's deficit, but not if it is funded by raising taxes. In other words, this is saying that there is a positive effect on an economy by borrowing more money and spending it in the economy, thereby increasing economic activity. My view is that this would be the case irrespective of whether the borrowed money would be spent on UBI or some other scheme. For me therefore, the article is somewhat irrelevant when considering the merits of UBI. There are merits to UBI even if it is funded by a method that doesn't provide expansion of the economy and those merits are what should be the focus for building support for the UBI concept, not the method of financing it (which is an entirely different and separable consideration for policy makers). The main benefits of UBI are a more secure safety net for citizens, the removal of financial fear from their lives and the opening up of opportunities for people to feel fully free to redirect their lives into what is most fulfilling (and often what benefits their communities) rather than what pays the basic bills. Global sustainability will only happen if the mainstream of the population live lives that are sustainable. That might seem like a trivial statement. But it has some fundamental questions underneath it. How and when will the mainstream accelerate the necessary shift from an unsustainable trajectory to a sustainable one?

The transition has started, but is not happening fast enough, as highlighted by Lord Stern in many talks and publications in the last few years, on the issue of Climate Change alone. And yet it goes much further than Climate Change. It is an issue of water, food, land use, consumerism. All these aspects require major shifts globally to achieve a just and sustainable future for all global citizens. The mainstream is the place where this shift will really happen. And if the mainstream doesn't "move" in the sense of changing its ways of living, travelling, earning, using energy, consuming, recycling, then the mainstream might have to "move" in a different sense - to physically move to find different places to sustain itself as increasingly dramatic deterioration happens in the places they currently live - resulting in mass migration on an unprecedented scale. The Global Commons (eg the air we breathe, the rain water, the oceans) are too important in sustaining all the global population to let their management be left to any one political party. Climate change and other challenges are best solved by cross-party working.

It could be a mistake to attach hope for sustainability solutions to one particular party. That lends itself to people taking the view that, because they don't support that particular party, they should give up on sustainability altogether in order to demonstrate loyalty to their chosen party. Best to make sustainability non-partisan, and to work to weave it into the fibre of all political parties. Our joint future on the planet is too big a thing to be left to become a political football. I wasn't able to attend this talk in person in Oxford earlier this month, but I caught the tail-end via the livestream video, and watched the whole of it later (link here). Lord Stern is optimistic, and points out that this is a topic where there is massive potential for cross-party support. He paints a picture of short-term investment in sustainable infrastructure to provide economic growth while moving to a net zero carbon economy in the next 40 - 50 years, supported by the Sustainable Development Goals. Urgency and scale of the transition were key emphases in his talk. We're moving much too slowly on this, and we need to speed up.

Amory Lovins gave an excellent talk about disruptive energy technologies at the Oxford Martin School earlier this week. I wasn't able to make it in person, but the talk, and the Q and A that followed it, can be seen here. After watching it, I'm more than ever convinced that we're witnessing a historic paradigm shift in the ways we produce, distribute and use energy, a shift away from carbon-emitting energy and towards a low-carbon energy future. Anyone who doesn't engage positively with this change will be swept away by it.

The UK snap General Election, and the forthcoming Brexit, is a massive distraction from global sustainability challenges. These challenges will still be there when the political dust has settled on the next two years of change (or is it lack of change of any relevance). Meanwhile, during that time I'll probably upgrade to a new Electric Vehicle with bigger range per battery charge and use my newly recycled greenhouse to grow more local food. Mundane things that help keep me sane when political developments in the UK and elsewhere look threatening, disturbing, and fail to provide the right kind of leadership on matters of social justice and sustainability.

I don't see it as being contradictory to any significant extent to have multiple identities, each of which comes to the fore in different strengths at different times depending on the circumstances. I'll say a little about my identities as an example.

Mostly, my identity as a worker comes to the fore during the working day, and my identity as a family member and carer come to the fore when at home or out and about with my family. But at other times (such as when writing this blog) my identity as a global citizen comes naturally to the fore. It also appears at other times, for example when with work colleagues who have similar dreams for a better future for global humanity. I also have an identity as a financial professional - the sort of person who many people look to for advice on the state of the organisation's finances. The Planetary CFO role holds a particular fascination for me because it lies at the intersection of almost all these identities. And where there are minor conflicts between identities, I find it leads to a creative process, and a source of diverse thoughts in trying to reconcile the interests of each identity in conflict. Some might see a risk here of lacking stability, of becoming a chameleon and changing to suit each circumstance, through resolving the identities in favour of the one that most effectively blends into the surroundings it finds itself in. However, I prefer to see it as learning to change and adapt, through one's experiences and responses to those experiences. We need more change in human systems if we're to solve the massive environmental and social justice challenges we all face. We can do a lot worse than reflect on our own capacity to change and to challenge the status quo in our own lives. In the mythological battle between the immovable object and the irresistible force, my money's on the irresistible force, every time. |

AuthorThe Planetary CFO - working towards a sustainable World Balance Sheet. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|