|

Video of an excellent summary about Natural Capital by Dieter Helm at Irish Natural Capital Forum October 2016 here.

I didn't attend myself, but the video records Professor Helm's 30-min talk and Q&A. Prof Helm is Chair of the UK's Natural Capital Committee. Some wonderful soundbites, eg "No country in Europe currently has a Balance Sheet" (9mins 30). and "better to be roughly right than precisely wrong" (11 mins 45 to 12 mins 15). Accountancy isn't just for business, it's for the environment" (About 20 mins).

0 Comments

The UK's Natural Capital Committee continues to advise Government on how the 25 Year Environment Plan can be created in such a way that the environment we leave to our children is no worse than the one we inherited ourselves.

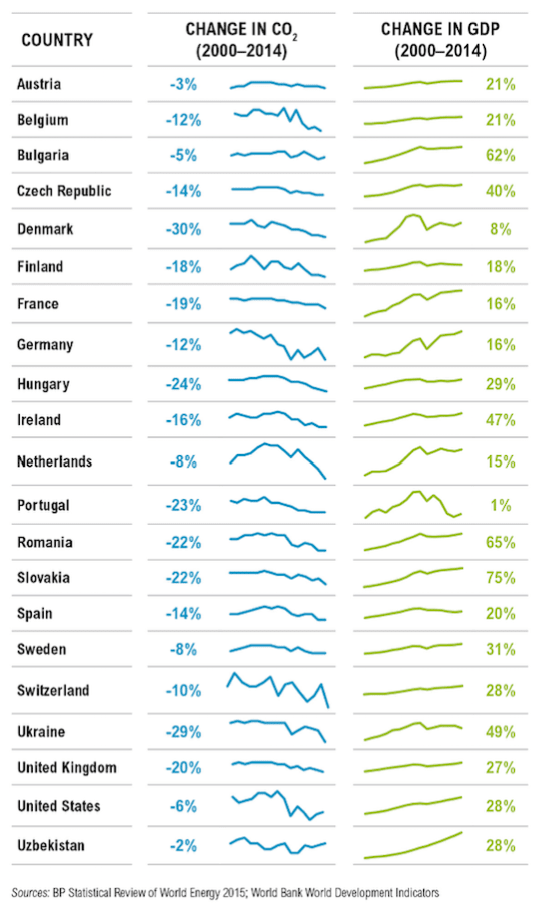

The Committee's 2017 report on this can be found here. The Planetary CFO will be keeping an eye on how the 25 year plan shapes up, because merely stopping the decline is not going to be good enough in the longer-term. We will need a co-ordinated world-wide plan for the environment globally, for a sustainable environment to provide well for peak global population of, perhaps, 10 billion. Just to signpost, some of the key elements of this debate are at: http://www.carbonbrief.org/the-35-countries-cutting-the-link-between-economic-growth-and-emissions and: https://steadystatemanchester.net/2016/04/15/new-evidence-on-decoupling-carbon-emissions-from-gdp-growth-what-does-it-mean/ Much of the debate was triggered by the following infographic from Carbon Brief. The core of the debate is about the accuracy of the data and the extent to which it might suggest causality, or just correlation without causality (instead). Also, more detailed analysis of the data might suggest that there are other factors involved rather than a simplistic, direct link between carbon emissions and the carbon-intensity of production and consumption patterns in the listed countries. For example some offshoring of carbon-emitting production processes would tend to reduce the territorial carbon emissions of the listed countries but increase the carbon emissions of other countries not listed without affecting GDP per se. This offshoring might represent a significant part of the explanation of the headline trends, throwing doubt on the headline suggestion that carbon emissions are decoupling from GDP. To allow for these effects, it would be good to see the global total GDP trends and carbon emission trends, rather than just data on each of these for a few selected countries. There is some global data reported in the Guardian at:

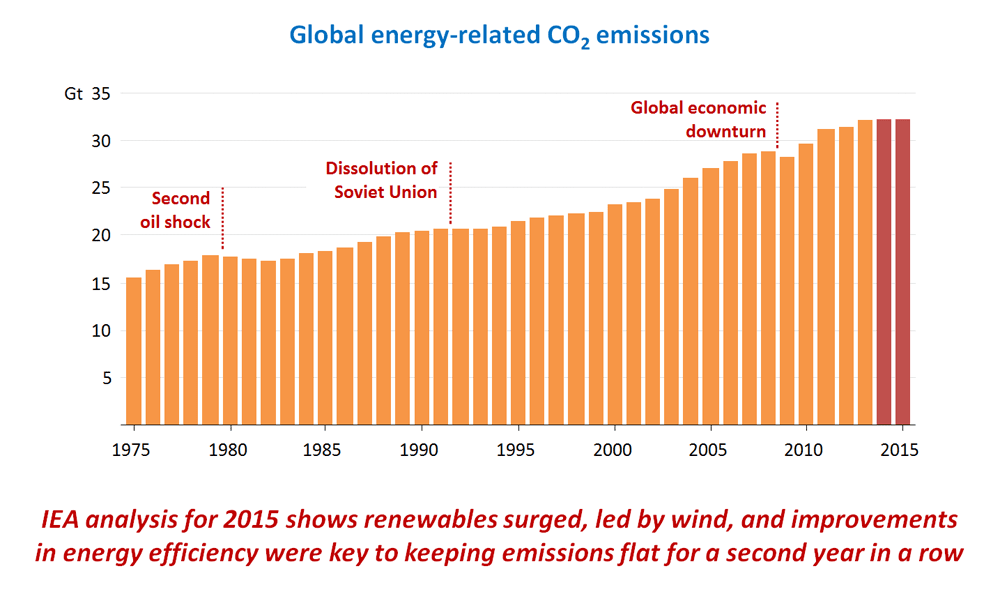

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/apr/14/is-it-possible-to-reduce-co2-emissions-and-grow-the-global-economy and this suggests that one factor is that Chinese energy production from coal has recently been growing less rapidly than in the past, and so there is some hope for a green revolution in China. But it appears to be quite difficult to get a comprehensive picture of all the various factors linking carbon and GDP and the cause-and-effect relationships between all of them. Perhaps, also, longer-term data needs to be collected and analysed before more confidence can be built in any conclusions reached. A starting point for this might be an IEA article at: https://www.iea.org/newsroom/news/2016/march/decoupling-of-global-emissions-and-economic-growth-confirmed.html and, in particular, the following highlights, albeit discussing only the most recent two year period when there appears to have been global GDP growth but without much increase in global carbon emissions: "Global emissions of carbon dioxide stood at 32.1 billion tonnes in 2015, having remained essentially flat since 2013. ... In parallel, the global economy continued to grow by more than 3%, offering further evidence that the link between economic growth and emissions growth is weakening." Of course, a trend over two years is not very conclusive in this complex area, which is why I make the comment above about the need to look at trends over much longer timeframes, perhaps even decades. Creating a sustainable future for all global citizens is too important a matter to be derailed by political point scoring. It transcends political ideologies. Global Climate Change doesn't care about the political persuations of the people it kills. The challenge is to ensure that the transition to sustainability proceeds without undue political interference. It would help if all political parties would agree on some of the key elements, eg decarbonisation, water and food security and enhancement of Natural Capital. That way, no party could use these matters to try to make their manifestos different from those of other parties and win votes from them.

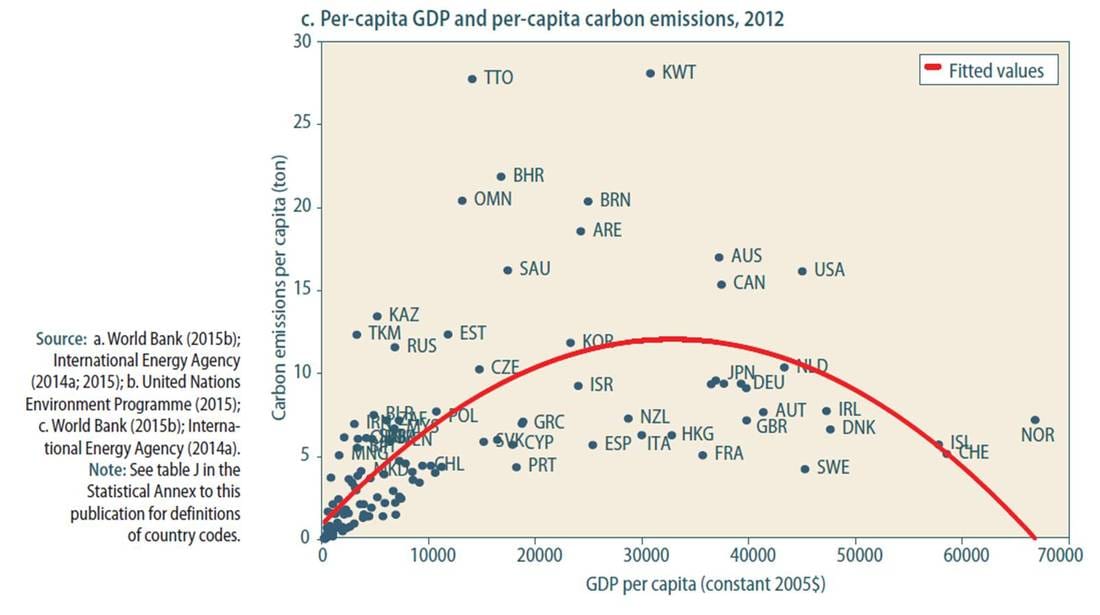

The diagram above is from "World Economic Situation and Prospects 2016" published by the UN. On the face of it, this provides some hope about the state of decoupling of carbon emissions from per capita GDP. If sufficient decoupling can be achieved, then an amount of aggregate global GDP growth could be achieved while keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

However, there is one aspect of this which is of some concern. There is a nagging question on my mind. What if the reduction in per capita carbon emissions in high-GDP countries is largely achieved by 'exporting' carbon emissions, ie by consuming products and services imported from parts of the world which have much higher per capita carbon emissions? If this was the case, then, all other things being equal, it wouldn't be possible for all countries to be moved, over the years and decades, from bottom left of the diagram to the bottom right. This is because there wouldn't be any countries remaining in the bottom left to "export" carbon emissions to. I'd be happy if anyone can point me in the direction of evidence that can put my mind at rest on this point. And perhaps one of the most important questions following on from that is: "what would be the distribution of countries on the above curve at a sustainable equilibrium, and would that equilibrium be consistent with operating within sustainable and safe planetary limits (as per the Oxfam sustainability "doughnut" model)?" Achim Steiner (above), new Director of the Oxford Martin School, gave an absorbing and curiously upbeat talk in Oxford on 29th November about many of the dimensions of the current global challenges in creating a sustainable, fair existence for humanity on the planet.

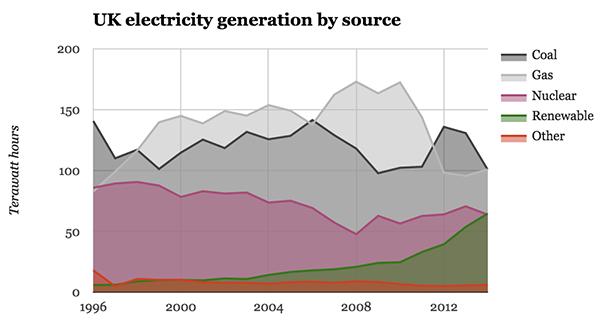

He argues not for throwing away the existing systems, such as global economic ones, but rather for tweaking them in ways that incentivise right behaviours that take us closer to sustainability for the common good. His most impassioned plea was for members of the audience to consider the degree of pressure currently faced by farmers, especially smallholders, within the agricultural economy. He pointed out that we need that sector to thrive if we are to feed a human population that might grow to 10 billion people. he also emphasised that automation is a threat to employment, yet within a few decades we will need about 600 million new jobs if we are to continue to use employment as an important means for people to provide for themselves. Although this was one of the best, most integrative talks I've ever attended, I'm left with one question that bugs me - how to turn the fine words into fine actions. Indeed, that's a question I ask of myself as well as wonder about others. The video of the talk can be accessed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eiXHz8tOXfM This diagram is part of the reason I'm happy to use an Electric Vehicle in the UK - The mix of energy generation which provides the electricity I charge it with is moving rapidly from fossil fuels to renewables, from high carbon emmitting sources to low or zero emitting sources. Also, I have solar panels on my house, so some of the time I'm using locally generated electricity to charge the car rather than drawing it from the grid.

So-called "health tourism" is in the news a lot, painted as a large problem in the UK. The Planetary CFO's answer to this is that it wouldn't be such a large problem if a Global Health Insurance scheme was in place, agreed between all countries of the world, along similar lines to National Insurance in the UK. A global scheme would start providing basic health and wellbeing services for all global citizens, from the moment of birth (irrespective of the place of birth) and in any place in the world where they are at the time they need those services. A hospital in one county in England doesn't refuse treatment to someone who lives in another county, so why should we draw such distinctions for people from other countries?

A Global Health Insurance scheme would generate larger flows of money into the health systems of the world, which would provide larger resources for maintenance and investment, for example for scaling up to reduce waiting times, or expanding provision geographically. Investment in health facilities funded by such increased money flows would strengthen the assets within the non-natural capital section of the World Balance Sheet, making it easier to provide basic health and welfare services to all global citizens. When we say we value something, it usually means we’d rather not lose it, or lose the access to it or the ability to experience it. Or perhaps we gain something from being able to use it, and we lose something if we lose the use of it. And the more difficult it would be to restore it or replace it, the higher the value we would place on it, perhaps. This multiplicity of perspectives gives rise to a variety of ways of “placing a value on it”. For example, a monetary value we ascribe to an object might represent: · The original cost of producing it, if we made it ourselves – including amounts for our time and effort as well as all the raw materials, energy and other inputs to the processes used (historic cost) · The amount we paid for it if we bought it rather than making it ourselves (purchase cost) · The cost of replacing it if it is lost or destroyed (replacement cost) · The cost of alternative means of satisfying the same need or desire that it fulfils (a substitution value) · The money that could be obtained by preparing it for sale and then selling it (realisable value) · The price at which it can be bought or sold in its current state in a perfect market (market value) · The amount we could claim from an insurance company if it was lost in an incident covered by insurance (insured value) · The total of all the future discounted cash in-flows and out-flows generated by the expected future use of the object until it reaches the end of its useful life (the Net Present Value, or economic value) Of course, in most circumstances, for a specific object, all of the above approaches would result in a different value being ascribed. The method we use therefore becomes very context-dependent. In a sustainability context, the most concerning disjoint between such valuations would occur when someone owning or controlling a part of the Natural Capital places the wrong kind of value on it. For example, rainforest that has taken millennia to evolve and achieve a balanced and healthy ecosystem state should be valued at replacement cost, which is very high because of the immense amount of time and effort that would be required to replicate the patient construction of the ecosystem by nature. The realisable value or market value might be much lower because there is much less effort and time required to cut down the trees and sell the wood to someone than there is to grow a healthy ecosystem. Therefore, the method of valuation chosen very much depends on the purpose for which it is being done. There is a big difference between approaches appropriate for valuing something for the purposes of maintaining it within healthy ecosystems, within a sustainable custodianship role and approaches for valuing something for the purposes of serving market objectives or generation of business profits. Valuing such assets at replacement cost, but only while they remain in their natural state, and valuing them at a substitution cost if they are removed from that ecosystem (eg by being cut down and converted into raw materials) is necessary. This prevents the Tragedy of the Commons, by ensuring that as essential natural assets become scarcer, they become more and more highly valued for the purposes of conservation, and less and less valuable for the purposes of being converted for alternative use outside the ecosystem. That duality of perspectives on the same object is a necessary step in order to reconcile the need for conservation alongside the need for sustainable harvesting and use of resources in sustainable ways for humanity to co-exist successfully with natural ecosystems in perpetuity. An important part of this consideration is clearly the question of who owns or controls assets, which is linked to who is allowed to own or control them. The Global Commons (eg the air we breathe, the water we drink, the basic food that sustains us, the ecosystems that provide some of these, and so on), because of their essential role in maintaining sustainability of life on Earth, cannot be allowed to be owned or controlled by interests that would breach sustainability limits. The global custodian could legitimately fine anyone who converted such assets (eg by cutting them down for wood) by charging them the difference between the replacement cost and the substitution cost (as described above). A proviso on this is that there exists the means to apply the revenue from such fines to undertake that patient replacement activity, while what remains of the assets of that type is sufficient to maintain ecosystems within sustainable ranges. The success of this approach depends on adequate prevention, detection and policing of acts giving rise to such fines. Part of the deterrence would be the size of the fines resulting from the above methods of calculation. We hear a lot about efficiency, but not enough about circular economy. Which is strange, because circular economy is a no-brainer in my view. Starting a conversation with efficiency is starting in the wrong place, in a use-it-up and throw-it-away kind of place. Starting a conversation with circular economy starts it in a better place.

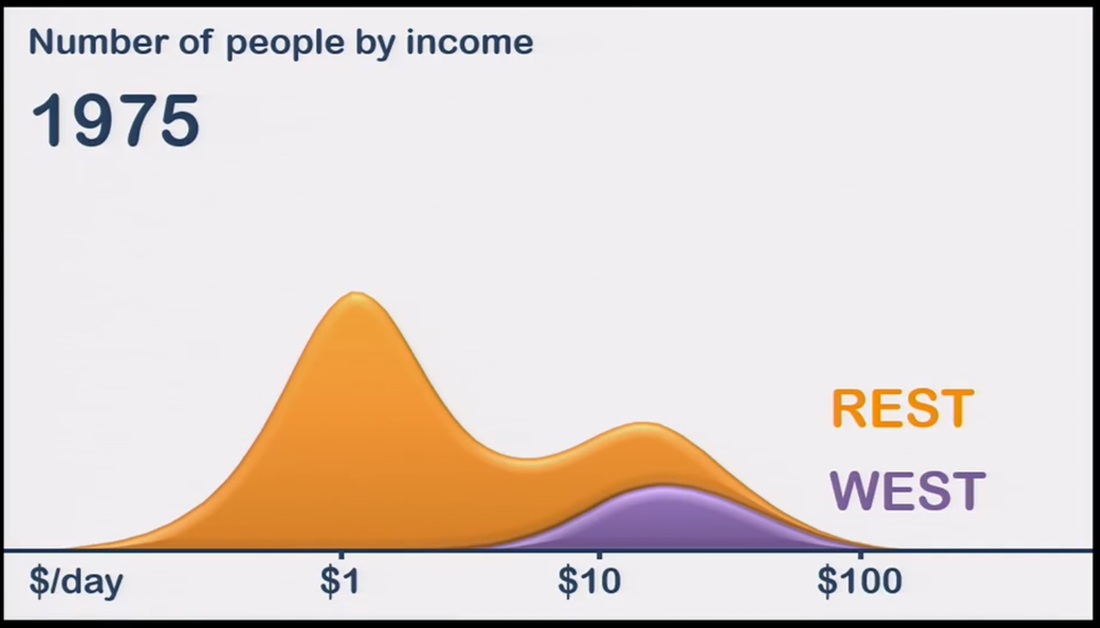

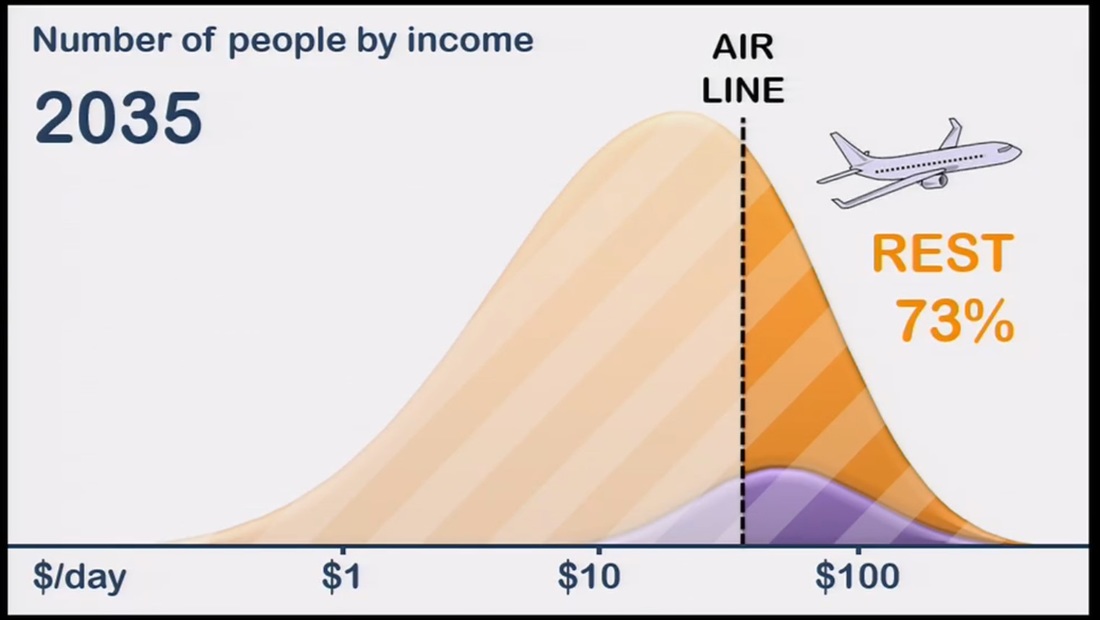

First we had recycle, when we knew we had to reduce the amount of stuff being "thrown away", usually into landfill. Then we had repair and recycle. Why throw it away at all if you could repair it, delaying the inevitable moment when it would have to be thrown away? Then we had reuse, repair and recycle, when we could turn an existing object to a new use, or repurpose it, when it was no longer suitable for its previous use. Then we had reduce - use less of something - less in equals less to throw away at the end. All these were about efficiency - reducing the amount thrown away for each unit of material that was an input to produce a thing we first started to use. So we had reduce - reuse - repair - recycle. Now we need to reconceive - to re-imagine the whole. Not just the inputs and outputs from a process, but a holistic approach to our need/want and how it is satisfied (or redirected) between self and surroundings. That's what will bring a circular economy. When the first question is about the relationship between self and non-self. Between Me and Us and All (all living things, all material things and the only world we will ever fully experience - the planet). In this re-imagining, we are not only served by the circular economy, but we are also a servant to it as well. In the same way that there are numerous symbioses in nature, we are part of the circular economy, contributing to it as well as receiving from it. This is a new mindset. One that will help us find a sustainable future together, rather than a narrow, efficient but ultimately unsustainable one. Yesterday I saw a TED talk about the ignorance project by Hans Rosling of the Gapminder Foundation: https://www.gapminder.org/ignorance/ Below are two screenshots showing their views on what others might call the 'economic growth lifts all boats and reduces inequalities' argument. Two humps become one. This is all well and good regarding reducing inequality, although they do point out that this still means there is forecast to be an enormous number of people in abject poverty.

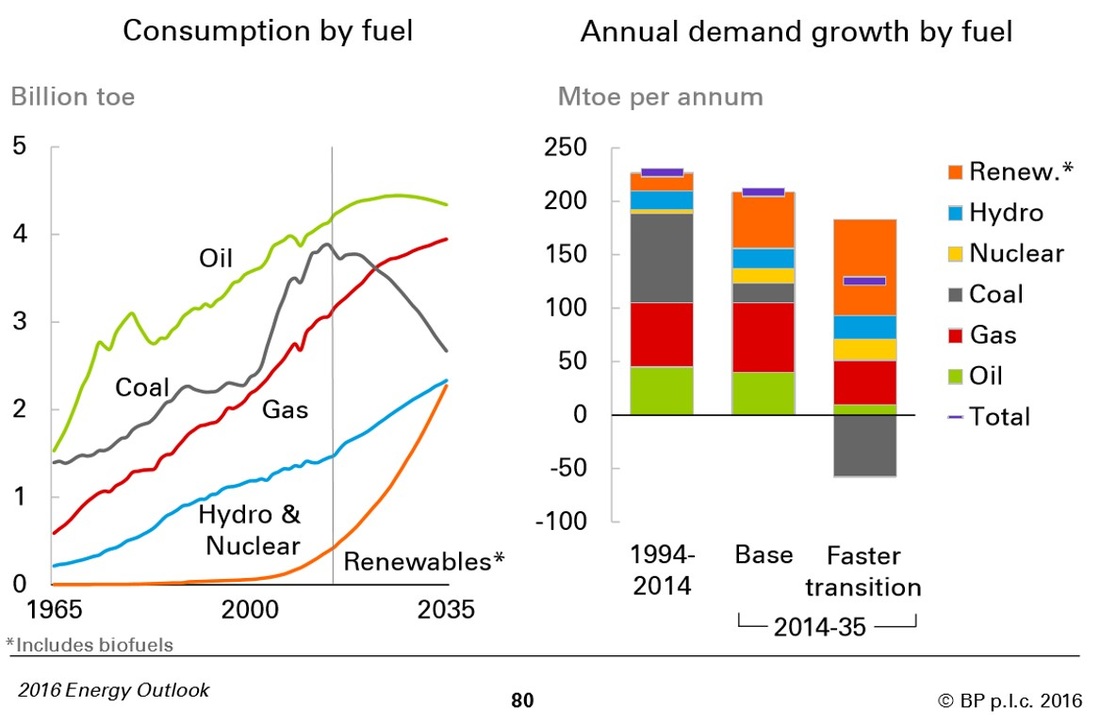

But one thing that is not mentioned in the talk is the likelihood that the economic growth behind the assumptions these data and forecasts rely on might bump up against planetary sustainability limits. The area under these curves represents, approximately, the total amount of global economic activity, for example for the year it shows. Unless we can break the strong link between economic activity and material throughput, if the area under the curve grows too big, we will push through the safe and sustainable limits of our planet. We currently have a situation of unburnable carbon, which gave rise to the 'keep it in the ground' campaign from the Guardian. How long before we might need an 'unspendable money' campaign? The chart above is from the BP World Energy Outlook 2016. It's the most dramatic decarbonisation scenario of three scenarios they forecast through to 2035. It sees global carbon emissions (from the global energy system) peaking in about 2020 (roughly coinciding with peak oil). To the left of the thin grey vertical line are the actuals from 1965 to 2014. BP admits in their analysis that even this aggressive decarbonisation scenario does not achieve the IEA 450 (ie warming kept under 2 degrees) scenario. All BP's scenarios fail to meet that target. However, I think there are two remarkable things about this chart.

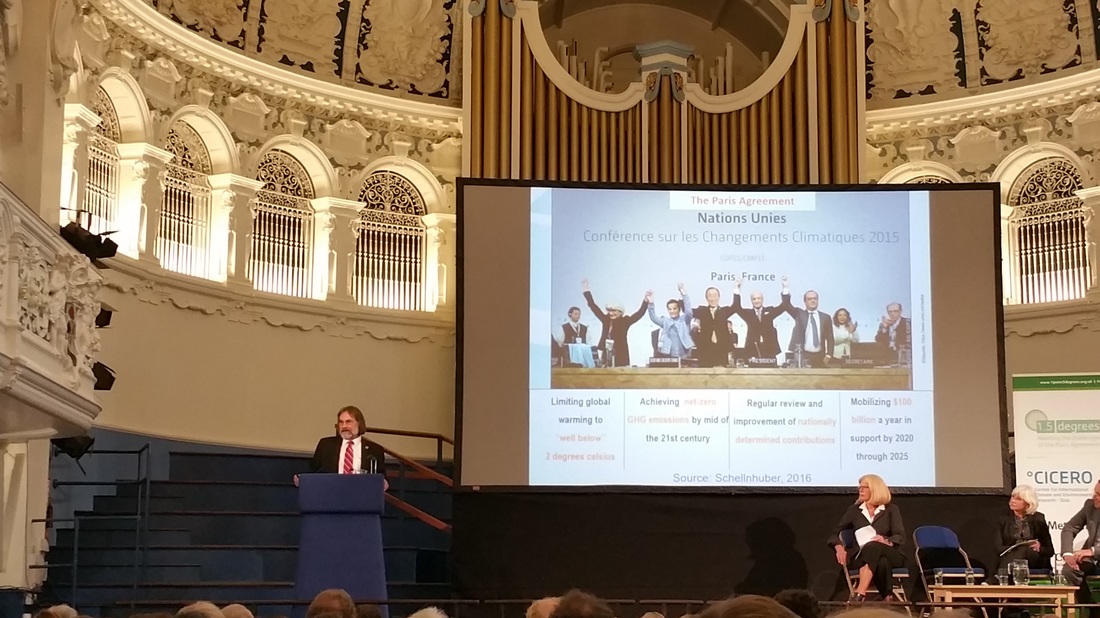

The first is that it shows that, for anyone planning for future investment in long-term energy infrastructure (for which there can be forty-year timeframes and Net Present Value calculations), it is no longer Business As Usual. The renewables energy revolution has already started. The second is that gas is clearly considered a growing fuel for a long time to come. I hope that includes effective CCS. As a final consideration, BP's forecasting models the total energy demand based on various assumptions about GDP and population growth (among other things). One way of moving closer to achievement of IEA 450 would be to influence energy demand so that future forecasts can be reduced. That would speed the demise of coal and could potentially reduce the forecast use of gas. Last night I went to the public launch of 1.5 Degrees: Meeting the challenges of the Paris Agreement - http://www.1point5degrees.org.uk/

Excellent set of talks, discussions and Q&A on meeting the challenges of keeping global warming to below 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. Will be interested to see the results of the rest of the conference, especially how the matter of global justice is treated, on top of the technical and geopolitical aspects. The pace of modern life in the mainstream is something most have become accustomed to. It has become 'the new norm' and it's part of the system with immense inertia driving us through sustainability boundaries.

This is like our perception when driving. When we drive fast, our brains get accustomed to that speed. It's as if our brains make decisions on less and less information from each object we pass, but turn their attention more to movements and 'strategic' matters such as the next junction or changing conditions. If we're not careful, we maintain this 'mode' even when we slow down, eg to enter a 30- or 20 mile an hour zone. As a result, everything seems to be moving so slowly when we do this, and sometimes it feels like we're going at 10 instead of 30. The natural inclination, if we weren't taking notice of speed limit signs, would be to still be travelling at 40 or 50 but thinking we were travelling at 30. I read about this effect a few years ago, and then consciously looked out for it, checking myself against speed limit signs before arriving in the next speed zone, and realised that it was a real effect. Without having been primed to look out for it, I might never have noticed it. Unsustainability is a little like this. Unless we check ourselves against it, the tendency is for the speed of modern 'developed/advanced' existence, built on efficient systems of exploitation of natural and ecological resources, and grown largely on the back of fossil fuels and a growth model of the economy, to be something we become accustomed to. Any 'slower', more sustainable existence feels too slow to even contemplate. So the mainstream juggernaut ploughs on ... At a social event recently, someone who works for an automotive manufacturer asked me If I could only change one thing, what would it be?

I had to think for what seemed like a few minutes but which must only have been tens of seconds. I'm grateful that he gave me that time. It wasn't that I didn't have something to say. It took that long to sift through a long list of things and try to work out what would be the key thing - the thing that would unlock everything else. I set out here a more extensive version of my answer than I gave at the time. I’d change the prevalent world culture from one of the self-interested individual to a benevolent collectivism. An ideal culture would not deny the rights of the individual to excel and achieve. But it would strike the right balance between the individual and the common good. The current socio-economic paradigm conspires against the development of this culture. Through economic slavery in many parts of the so-called developed world, people are kept under control. People are subservient to the overall goals of the state and big business, which include generating economic growth ad-infinitum and maintaining societal status-quo. People are compelled to be part of an immense and powerful machine that despoils the Earth’s seemingly bountiful minerals and ecological assets. They feel powerless to challenge the machine’s current form because they depend on it for sustenance in terms of the wages it provides and the systems it contains that deliver food, security, healthcare, education and so on. Although many people see the damage this system causes, they’re unable to imagine a viable alternative. Or perhaps they paint a mental image of a broken state and chaos combined with lack of social order. And they’re afraid of changes that might lead to this scenario. Unfortunately, in not taking action now to question the status quo, these people, who I suspect comprise a large part of the mainstream, are continuing to contribute to an ever-increasing probability that this very scenario unfolds. This is because of the continuing environmental unsustainability of the human systems they are propping up by their complicity with and in it. Perhaps they think the state will make all the right changes in time on their behalf to achieve sustainability “just in time” and protect their standards of living in the process. But they are wrong in thinking this, because it’s in the nature of the political system in most developed nations to ignore the long-term unless to do so would damage short-term political popularity. This is the inertia of the unchallenging majority. This is what prevents real change from occurring until a crisis point comes along which can no longer be ignored. One of the challenges for sustainabilitarians is to set out a compelling vision of a sustainable future and to help people in the mainstream to identify with it, to want it to happen (or at least their own version of it), to make their own minds up about how far we are away from it and the things that are currently keeping us on course for unsustainability but which could be changed if there was sufficient popular support. The prevalence of a more collective culture would be the key to providing fertile ground for this vision to take root and eventually flourish. I've heard quite a few reports in the media that one of the main reasons many people voted for Brexit was to protect a sense of local community. The claim is that the sense of community is being eroded or swamped by the rate of immigration.

This very much depends on your point of view about what "community" means. Is it a fixed or nearly-fixed set of people in a specific geographic area who already know each other well as neighbours, or is it rather a concept and an approach to our neighbours, whoever they are? The former view lends itself to increasing isolationism and protectionism. The latter view lends itself to being good neighbours to everyone, whether at local, regional, national or global levels - many overlapping and interlocking communities, and ultimately a community of communities, such as that represented by the European Union. The UK has decided to leave the European Union.

I hope that, in the ways this decision is carried out, those who do it draw on British values and identities that are admired by many around the world - tolerance, compassion, innovation, open-mindedness, free expression, love of diversity and opportunity, humility, respect for others, a spirit of both adventure and co-operation in seeking to solve world problems. This ushers in a period of renegotiation of the relationship between the UK and the rest of Europe. I hope that relationship, even if rocky in the short-term, emerges better - to the mutual benefit of all countries and peoples, in the context of our shared responsibilities for the Global Commons and each other. Barbara Hammond (Low Carbon Hub), Gemma Adams (Forum for the Future) - both pictured above - and Mike Barry (Marks & Spencer) gave thought-provoking talks about this topic this evening at the Said Business School and then led discussions. Fascinating glimpse into the minds of people in big business and of people working to encourage local community-owned renewable energy generation, and a range of topics surrounding these.

It was good to chat afterwards in unstructured conversations, eg to share ideas about what a sustainable zero-net-carbon world might look like, in Oxfordshire and beyond. Recently, people have responded positively to the IEA’s news that there are a number of countries where there appears to have been some degree of decoupling of carbon emissions from economic growth. For example, Carbon Brief have commented about it here:

http://www.carbonbrief.org/the-35-countries-cutting-the-link-between-economic-growth-and-emissions This got the Planetary CFO thinking about how this relates to finite/closed system aspects of our planetary home. Decoupling is a good thing, but not sufficient of itself to prevent us making our home uninhabitable by a civil and multitudinous human population. What really matters is whether the cumulative atmospheric carbon can be kept within an absolute limit to prevent runaway climate change switching the Earth into a new and much less survivable equilibrium state. Hence we need a cumulative carbon budget, and hence human-generated carbon emissions need to be close to zero within the next couple of generations. There is also the matter of “leakage” – where some countries might be reducing their emissions, but importing more goods from elsewhere with high embedded carbon emissions, which means that they are effectively exporting their carbon emitting behaviours to the countries they import those goods from. A graph, for a particular country, showing its economy growing and its carbon emissions falling might be a little comforting, 35 countries even more so, but it is far from showing that the battle for sustainability is being won. here to edit. TVs “Big Questions” - How to convince Sceptics it’s time to act on Climate Change – debate polarised23/3/2016 Last Sunday, I watched “The Big Questions” on TV. The title of the question gave me cause for optimism that the debate had moved on from a similar one a couple of years ago, in which there was too much airtime allowed for climate change denial, and not enough for healthy scepticism about the pace and size of the changes and the scale of the response necessary and genuine debate about ‘how much, how soon’ to rein in carbon emissions and start to capture carbon more effectively, and what sort of cumulative carbon budget would be appropriate for humanity.

However, I was disappointed when Nicky Campbell was not firm enough in stepping in to control an obvious climate change denier who, several times, took the airtime without invitation, spoke over other people, very loudly expounding complete denial that global warming is happening (saying things like “the Earth is cooling!” and “the source of the global warming campaign is religious”). To be fair to Nicky, he did then refer back to two of the environmentalists in the room (from Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth) asking them “how do you persuade someone like this that climate change needs action now?" And I was pleased to hear them respond with a challenge in return along the lines “it is ridiculous to give airtime to the extreme views of climate change deniers because the things they argue about are beyond debate – they are established fact – entering into an argument with them is not a debate – it is not going to change their minds – it polarises discussions and distracts from what we need to be talking about”. Overall, the sense I got from what happened in the programme was that it was not a debate about how to persuade genuine sceptics but rather an object lesson in how frustrating it is when climate change deniers get a platform and exchanges become polarised. This is what Nicky Campbell failed to head off. It's important to distinguish between genuine scepticism and denial. Would the same programme have allowed someone to be so vociferous in denial on other matters of established fact, for example to say "smoking tobacco causes no harm - in fact it's good for you", or "seat belts do not make you safer in a car accident". Scepticism is healthy - it helps us to challenge everyone on the actions we take - which actions, how far, how fast. But denial just creates unproductive and frustrating polarisation. |

AuthorThe Planetary CFO - working towards a sustainable World Balance Sheet. Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|