|

I've just published the World Balance Sheet 2018 here. This is an illustrative example intended to spark debate and ideas, rather than a finished or perfect object. Very few people have even attempted to create such a balance sheet. I've built on the work of one of those who has - Harald Deutsch - amending it and enhancing it through a lens of sustainability, for example by adding in natural capital. What my world balance sheet shows is that there is a significant "asset stewardship shortfall" of about USD 600 trillion. This arises mostly from degradation, and drawing down, of natural capital to meet humanity's aggregate consumption. I think the overall message is clear - we need to repair, enhance and maintain adequate natural capital to reduce the asset stewardship shortfall and eventually restore the balance in the world balance sheet.

0 Comments

The consultation is a first step in the right direction. It sets out the proposed new legislation as a means to make supply chains more sustainable, by requiring large companies to undertake due diligence on their (global) supply chains regarding the sustainability of the harvesting of commodities (eg timber) from forests. However, inevitably this will initially fall short of being optimum for sustainability. This is because it is currently expressed in a form that represents a type of "weak sustainability".

Thresholds (for the scope of the legislation) should be set to cover a specific proportion of the amount of forest risk commodities involved in the UK economy. Those thresholds and proportions should be reviewed and revised every few years, and progressively tightened until the point of diminishing ecological returns. I believe in "strong sustainability" and would recommend moving as swiftly as possible from the initial position to a position where the sum total of the world's natural capital is maintained and improved to a point of being optimal. This will go beyond many nations' existing laws, and will need to be backed up by new international laws. I participated in an A4S webinar yesterday on "Measure What Matters: Capitals Accounting". It was an excellent opportunity to engage with a network of CFOs on some of the big issues relevant to accounting and sustainability.

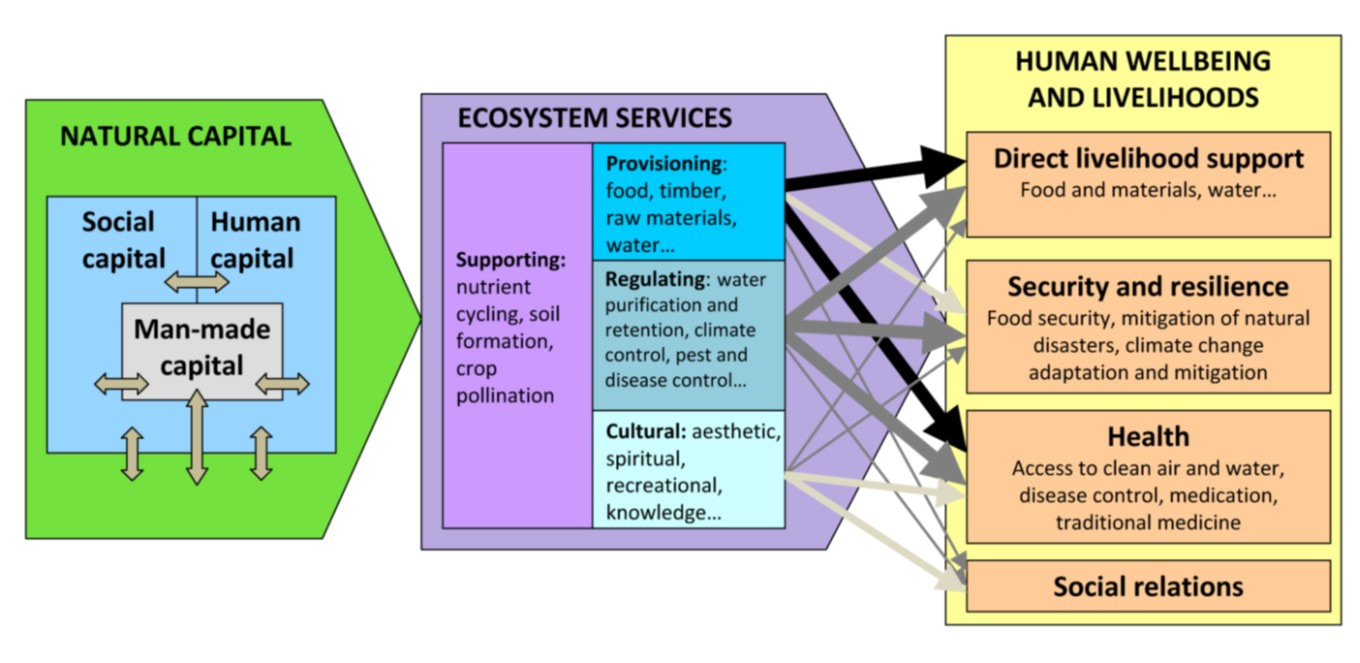

One of the discussion points was about substitutability of capitals, and, in particular, whether Natural Capital should be substitutable for other forms of capital. For context, the diagram above is from TEEB (2018) "Measuring what matters in agricultural food systems". The diagram was adapted by the authors of TEEB (2018) from an original source, which was the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 Synthesis Report. The general view from the webinar leaders/panelists, including a representative from TEEB, was that Natural Capital should not be substitutable for other types of capital. Full stop. No ifs, no buts. Natural Capital should be maintained (even enhanced) and not converted into other types of capital (for example, produced capital or financial capital). This draws on (and is almost a definition of) a concept of Strong Sustainability, rather than Weak Sustainability. Strong Sustainability is a concept I support, as a suitable response to the mounting evidence that generations of people have not just neglected but caused massive amounts of destruction and degradation to Natural Capital around the world, pushing us far into ecological overshoot, as highlighted very graphically by Earth Overshoot Day. It also means that individual businesses, as well as all other types of organisation, when assessing their impacts and dependencies, should carefully and separately identify the distinctions between the goods and services which Natural Capital provides as inputs to their business models, as distinct from the Natural Capital which provides them. (This is something that many organisations have been woefully poor at doing throughout modern history). They must not degrade or deplete the Natural Capital, for example by causing goods and services drawn from Natural Capital sources to exceed that which can sustainably be produced by that Natural Capital in perpetuity. Also, they must not allow their business processes to cause more carbon emissions, other waste or damage than can be sustainably accommodated by the Natural Capital in perpetuity. At an aggregate global level, the development of a World Balance Sheet will help us to assess whether the combined activities and impacts of all organisations, whether businesses or not, are complying with these requirements. The whole of the world's Natural Capital will be a key component of the World Balance Sheet. See more about the World Balance Sheet concept in my previous blog posts and at WorldBalanceSheet.com. On that site, I list my recent books, published this year, which go into more details about the emergence of the World Balance Sheet concept. These are very early days for the World Balance Sheet, but my hope is that we will rapidly reach the point where it will tell us whether enough people are practising Strong Sustainability to make a real difference in the transition to a just and sustainable future for the whole global population, today and in perpetuity. Land

In this article, I will argue that land, one of the most important but scarce (ie finite) assets on the planet, is undervalued and over-exploited. This is one of the key reasons we face continuing degradation of the biosphere, damaging the long-term sustainability of ecological systems and therefore threatening our own ability to survive and thrive in perpetuity. But I will also point out that some of the key building blocks for addressing this set of challenges are already in place. All we need to do is link up the disciplines of sustainability, ecology, accountancy and economics in a quest to place proper values on the assets and obligations associated with land ownership. But let’s start by looking at definitions. There is a high degree of consensus, in language dictionaries, on the definition of land, as shown by the following two examples: “The surface of the earth that is not covered by water” (Cambridge English Dictionary) “The part of the earth’s surface that is not covered by water” (Oxford English Dictionary) Although quite simple, these definitions are helpful in some ways, but unhelpful in others. Defining land by what it is not (not covered by water) helps to some extent with a ‘first approximation’ when assessing a part of the earth’s surface. We can ask “is it covered by water?” If the answer is “no” then it is, by definition, land. On the other hand, how far does the “land” extend below the surface (down through the soil and rock) or, for that matter, above the surface (up through the atmosphere and into space)? And does it include the living organisms that inhabit the land, the soil, the non-oceanic water and the air? Wikipedia gives us a rather more descriptive (if more wordy) definition, based on economics, and some inkling of key challenges surrounding ownership: “In economics, land comprises all naturally occurring resources as well as geographic land. Examples include particular geographical locations, mineral deposits, forests, fish stocks, atmospheric quality, geostationary orbits, and portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Supply of these resources is fixed ... Because no man created the land, it does not have a definite original proprietor, owner or user. “No man made the land. It is the original inheritance of the whole species.” (John Stuart Mill) As a consequence, conflicting claims on geographic locations and mineral deposits have historically led to disputes over their economic rent and contributed to many civil wars and revolutions.” There follows a quite typical current “economic” view on land and how it is treated in most economic calculations. Excerpts from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/land.asp -------- excerpts start ------------------------- Land By JAMES CHEN Updated Jun 4, 2020 What Is Land? Land, in the business sense, can refer to real estate or property, minus buildings, and equipment, which is designated by fixed spatial boundaries. Land ownership might offer the titleholder the right to any natural resources that exist within the boundaries of their land. Traditional economics says that land is a factor of production, along with capital and labor … Land qualifies as a fixed asset instead of a current asset. ... More Ways to Understand Land In Terms of Production The basic concept of land is that it is a specific piece of earth, a property with clearly delineated boundaries, that has an owner. You can view the concept of land in different ways, depending on its context, and the circumstances under which it's being analyzed. In Economics Legally and economically, a piece of land is a factor in some form of production, and although the land is not consumed during this production, no other production - food, for example - would be possible without it. Therefore, we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production. [I’ll provide a criticism of this interpretation below] Despite the fact that people can always change the land use to be less or more profitable, we cannot increase its supply. Characteristics of Land and Land Ownership Land as a Natural Asset Land can include anything that's on the ground, which means that buildings, trees, and water are a part of land as an asset. The term land encompasses all physical elements, bestowed by nature, to a specific area or piece of property - the environment, fields, forests, minerals, climate, animals, and bodies or sources of water. A landowner may be entitled to a wealth of natural resources on their property - including plants, human and animal life, soil, minerals, geographical location, electromagnetic features, and geophysical occurrences. Because natural gas and oil in the United States are being depleted, the land that contains these resources is of great value. In many cases, drilling and oil companies pay landowners substantial sums of money for the right to use their land to access such natural resources, particularly if the land is rich in a specific resource. … Air and space rights - both above and below a property - also are included in the term land. However, the right to use the air and space above land may be subject to height limitations dictated by local ordinances, as well as state and federal laws. … Land's main economic benefit is its scarcity. The associated risks of developing land can stem from taxation, regulatory usage restrictions … and even natural disasters. ------- excerpts end ---------- I would take strong exception to Chen’s statement that “we may consider land as a resource with no cost of production”. This treatment of land would be to grossly abuse it and under-value it, both in pure economic terms but also in terms of encouraging accelerating environmental degradation. In direct contrast to Chen’s description of land’s role in production, I would argue that land needs to be restored and maintained in a sustainable state that not only supports any economic production that relies upon it, but also so that the land performs, in perpetuity, its proper role as part of earth’s living biosphere. Accounting Guidance The International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”), and the International Accounting Standards (“IAS”) set the international frameworks guiding all accountants around the world in what is deemed to be acceptable ways of accounting for everything that appears in a balance sheet or a profit and loss statement. An example is the way assets are valued and reported. There are a number of accepted ways of attributing, or calculating, a value for an asset, including “land”. In accounting guidance, land is included in “property, plant and equipment”, being a particular type of “property”. Excerpt from IAS 16 ---------------------------- Property, plant and equipment are tangible items that: (a) are held for use in the production or supply of goods or services, for rental to others, or for administrative purposes; and (b) are expected to be used during more than one period. The cost of an item of property, plant and equipment shall be recognised as an asset if, and only if: (a) it is probable that future economic benefits associated with the item will flow to the entity; and (b) the cost of the item can be measured reliably. If the cost of land includes the costs of site dismantlement, removal and restoration, that portion of the land asset is depreciated over the period of benefits obtained by incurring those costs. Excerpts end ---------------------- From the excerpts above, we can build on what I have said about the obligation to maintain land to fulfil its role as part of a sustainable living biosphere. All that is required is to establish, and enforce, the principle of holding owners of land to account for maintaining the land sustainably. This needs to be backed up by national and international governance mechanisms (eg national and international laws and environmental regulations). When those governance measures are in place, then the asset value of any piece of land an owner wants to hold will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner. If the land’s current state is a long way below that which would be considered biospherically sustainable, then the value of the land might even be negative, because although the owner has an asset that will produce some positive economic value, for example from agricultural produce generated from it, there could exist a large obligation (liability) to set against that, representing the amount the current owner needs to spend to restore the land to a biospherically sustainable state. If the liability is larger than the value of the economic productivity of the land, then the land (asset) net value will be negative. It follows that the market price of any piece of land an owner wants to sell will reflect that sustainability obligation on the current owner and also the same obligation on the new owner. It is probably quite clear that, in the paragraphs above, I’ve based my arguments on a definition of strong sustainability when using the terms “sustainable” and “sustainability” etc. Can cryptocurrencies ever be recorded in a World Balance Sheet? Let's look at some of the key features of Bitcoin, as an example of a cryptocurrency:

According to wikipedia:

Although Bitcoin is (in theory) decentralised, wikipedia also says: "As of 2013 just six mining pools controlled 75% of overall bitcoin hashing power.[134] In 2014 mining pool Ghash.io obtained 51% hashing power which raised significant controversies about the safety of the network. The pool has voluntarily capped their hashing power at 39.99% and requested other pools to act responsibly for the benefit of the whole network.[135] c. 2017 over 70% of the hashing power and 90% of transactions were operating from China." Bitcoin isn't backed by any assets in the real world. Therefore, even though it is said that their design and implementation will result in a maximum of 21 million Bitcoins ever being created, they are only ever going to have a value determined by owners' and users' perceptions of value, not any related underlying value of real assets in the real world. This makes them even more ethereal than any national currency anywhere in the world, which at least has the benefit of some asset backing (albeit on a fractional banking ratio) underwritten by a real-world institution such as a national central bank. The risks associated with recognising the value of Bitcoins should be fairly obvious from this. There can be no confidence that their supposed value will continue to exist, and at any point they might become valueless. There is no authoritative body that can be called upon to take any action to stabilise the value of Bitcoins. Indeed, there is a risk that any such putative body that purported to be able to do so could be a fictitious body, or a legitimate body acting fraudulently or negligently. Exchanging any real-world national currency, or other assets, for Bitcoins represents, therefore, nothing more than pure speculation on the future value of an imaginary asset. For this reason alone "I'm out!" and I will not be recommending inclusion of any cryptocurrencies in the World Balance Sheet. Yesterday, I participated in this online meeting and discussion. There were talks by Ben Caldecott and Anna Olerinyova, followed by Q and A. I found this a fascinating discussion.

There is one exchange in the chat that I’d like to follow up on. At one point, another participant and I had a brief exchange about Steady State Economy, and they signposted a paper: “Another reason why a steady-state economy will not be a capitalist economy”, by Ted Trainer [University of New South Wales, Australia] http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue76/Trainer76.pdf The central tenet of Trainer’s paper was to say that Herman Daly had said that capitalism could not exist in a steady state economy unless there was considerable decoupling of economic growth from material throughput. The following is a quote from the paper: “... Daly’s case that a steady-state economy can remain capitalist depends entirely on the assumption that there is considerable scope for technical advance to enable productivity gains and decoupling, and for this to continue indefinitely” Trainer seems to be arguing that steady state economics is not enough, and supports an alternative called The Simpler Way, and that might be why he has taken quite a negative view on the supposed inconsistencies between Daly’s steady state economics and capitalism:. From Trainer’s paper (I have emboldened the most relevant text): “It should be evident from the above discussion that it is not sufficient merely to take a steady-state economy as the goal. When the seriousness of the limits to growth is understood, as the above multiples make clear, it is obvious that a sustainable and just society must have embraced large scale de-growth. That is, it must be based on per capita resource use rates that are a small fraction of those typical of rich countries today; it must in other words be some kind of Simpler Way. (For the detail see TSW: The Alternative.)” I’ve found a different source (Wikipedia) that suggests that this is perhaps a rather extreme interpretation of what Daly actually believes (or, at least, believed in 1980) – in which I’ve emboldened the most relevant text: “Fully aware of the massive growth dynamics of capitalism, Herman Daly on his part poses the rhetorical question whether his concept of a steady-state economy is essentially capitalistic or socialistic. He provides the following answer (written in 1980):’The growth versus steady-state debate really cuts across the old left-right rift, and we should resist any attempt to identify either growth or steady-state with either left or right, for two reasons. First, it will impose a logical distortion on the issue. Second, it will obscure the emergence of a third way, which might form a future synthesis of socialism and capitalism into a steady-state economy and eventually into a fully just and sustainable society’. Daly concludes by inviting all (most) people — both liberal supporters of, and radical critics of, capitalism — to join him in his effort to develop a steady-state economy.” Thought this might be useful as a counter, from Herman Daly himself, to what Trainer claims about him. Just discovered the work of Anna Rosling on "Dollar Street" - a visualisation of people's lives around the world, enabling us to see how people on a spectrum by income really live.

Here's the link: https://www.gapminder.org/dollar-street/matrix?thing=Homes&countries=World®ions=World&zoom=4&row=1&lowIncome=481&highIncome=843&lang=en The website also includes a TED talk by Anna, which explains how the material was collected and how it helps us to understand the similarities and differences generated by income and geography. Video of an excellent summary about Natural Capital by Dieter Helm at Irish Natural Capital Forum October 2016 here.

I didn't attend myself, but the video records Professor Helm's 30-min talk and Q&A. Prof Helm is Chair of the UK's Natural Capital Committee. Some wonderful soundbites, eg "No country in Europe currently has a Balance Sheet" (9mins 30). and "better to be roughly right than precisely wrong" (11 mins 45 to 12 mins 15). Accountancy isn't just for business, it's for the environment" (About 20 mins). The UK's Natural Capital Committee continues to advise Government on how the 25 Year Environment Plan can be created in such a way that the environment we leave to our children is no worse than the one we inherited ourselves.

The Committee's 2017 report on this can be found here. The Planetary CFO will be keeping an eye on how the 25 year plan shapes up, because merely stopping the decline is not going to be good enough in the longer-term. We will need a co-ordinated world-wide plan for the environment globally, for a sustainable environment to provide well for peak global population of, perhaps, 10 billion. So-called "health tourism" is in the news a lot, painted as a large problem in the UK. The Planetary CFO's answer to this is that it wouldn't be such a large problem if a Global Health Insurance scheme was in place, agreed between all countries of the world, along similar lines to National Insurance in the UK. A global scheme would start providing basic health and wellbeing services for all global citizens, from the moment of birth (irrespective of the place of birth) and in any place in the world where they are at the time they need those services. A hospital in one county in England doesn't refuse treatment to someone who lives in another county, so why should we draw such distinctions for people from other countries?

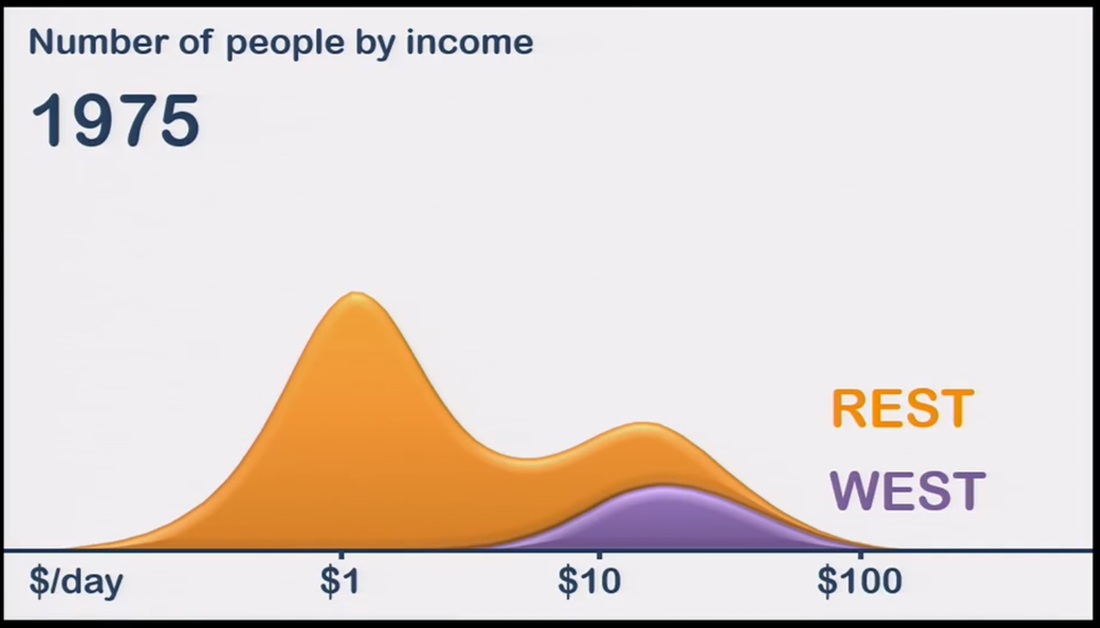

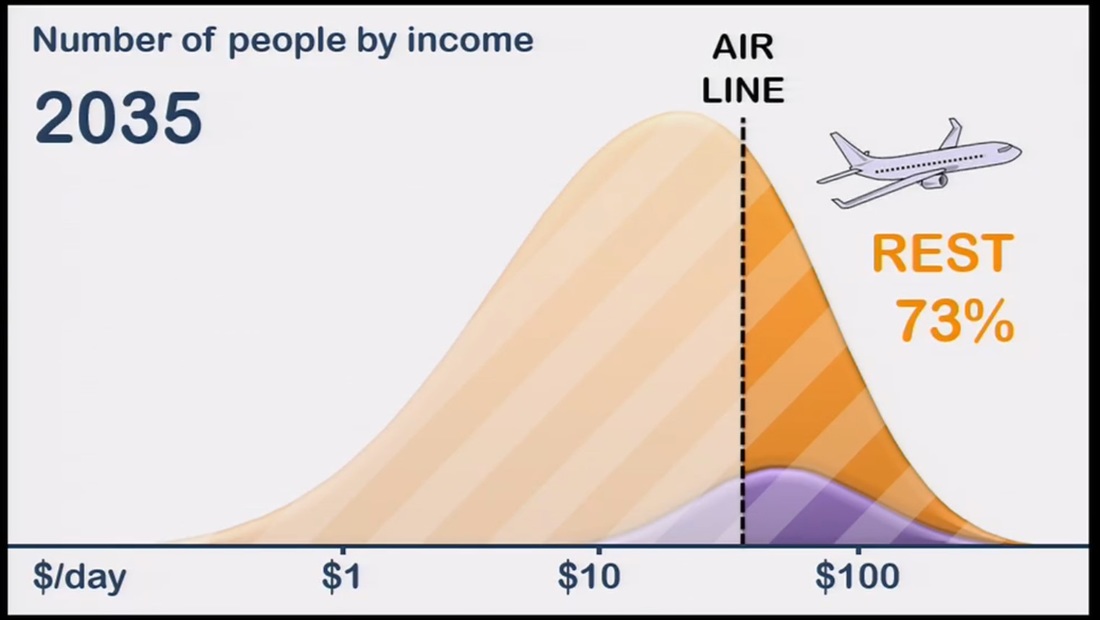

A Global Health Insurance scheme would generate larger flows of money into the health systems of the world, which would provide larger resources for maintenance and investment, for example for scaling up to reduce waiting times, or expanding provision geographically. Investment in health facilities funded by such increased money flows would strengthen the assets within the non-natural capital section of the World Balance Sheet, making it easier to provide basic health and welfare services to all global citizens. When we say we value something, it usually means we’d rather not lose it, or lose the access to it or the ability to experience it. Or perhaps we gain something from being able to use it, and we lose something if we lose the use of it. And the more difficult it would be to restore it or replace it, the higher the value we would place on it, perhaps. This multiplicity of perspectives gives rise to a variety of ways of “placing a value on it”. For example, a monetary value we ascribe to an object might represent: · The original cost of producing it, if we made it ourselves – including amounts for our time and effort as well as all the raw materials, energy and other inputs to the processes used (historic cost) · The amount we paid for it if we bought it rather than making it ourselves (purchase cost) · The cost of replacing it if it is lost or destroyed (replacement cost) · The cost of alternative means of satisfying the same need or desire that it fulfils (a substitution value) · The money that could be obtained by preparing it for sale and then selling it (realisable value) · The price at which it can be bought or sold in its current state in a perfect market (market value) · The amount we could claim from an insurance company if it was lost in an incident covered by insurance (insured value) · The total of all the future discounted cash in-flows and out-flows generated by the expected future use of the object until it reaches the end of its useful life (the Net Present Value, or economic value) Of course, in most circumstances, for a specific object, all of the above approaches would result in a different value being ascribed. The method we use therefore becomes very context-dependent. In a sustainability context, the most concerning disjoint between such valuations would occur when someone owning or controlling a part of the Natural Capital places the wrong kind of value on it. For example, rainforest that has taken millennia to evolve and achieve a balanced and healthy ecosystem state should be valued at replacement cost, which is very high because of the immense amount of time and effort that would be required to replicate the patient construction of the ecosystem by nature. The realisable value or market value might be much lower because there is much less effort and time required to cut down the trees and sell the wood to someone than there is to grow a healthy ecosystem. Therefore, the method of valuation chosen very much depends on the purpose for which it is being done. There is a big difference between approaches appropriate for valuing something for the purposes of maintaining it within healthy ecosystems, within a sustainable custodianship role and approaches for valuing something for the purposes of serving market objectives or generation of business profits. Valuing such assets at replacement cost, but only while they remain in their natural state, and valuing them at a substitution cost if they are removed from that ecosystem (eg by being cut down and converted into raw materials) is necessary. This prevents the Tragedy of the Commons, by ensuring that as essential natural assets become scarcer, they become more and more highly valued for the purposes of conservation, and less and less valuable for the purposes of being converted for alternative use outside the ecosystem. That duality of perspectives on the same object is a necessary step in order to reconcile the need for conservation alongside the need for sustainable harvesting and use of resources in sustainable ways for humanity to co-exist successfully with natural ecosystems in perpetuity. An important part of this consideration is clearly the question of who owns or controls assets, which is linked to who is allowed to own or control them. The Global Commons (eg the air we breathe, the water we drink, the basic food that sustains us, the ecosystems that provide some of these, and so on), because of their essential role in maintaining sustainability of life on Earth, cannot be allowed to be owned or controlled by interests that would breach sustainability limits. The global custodian could legitimately fine anyone who converted such assets (eg by cutting them down for wood) by charging them the difference between the replacement cost and the substitution cost (as described above). A proviso on this is that there exists the means to apply the revenue from such fines to undertake that patient replacement activity, while what remains of the assets of that type is sufficient to maintain ecosystems within sustainable ranges. The success of this approach depends on adequate prevention, detection and policing of acts giving rise to such fines. Part of the deterrence would be the size of the fines resulting from the above methods of calculation. Yesterday I saw a TED talk about the ignorance project by Hans Rosling of the Gapminder Foundation: https://www.gapminder.org/ignorance/ Below are two screenshots showing their views on what others might call the 'economic growth lifts all boats and reduces inequalities' argument. Two humps become one. This is all well and good regarding reducing inequality, although they do point out that this still means there is forecast to be an enormous number of people in abject poverty.

But one thing that is not mentioned in the talk is the likelihood that the economic growth behind the assumptions these data and forecasts rely on might bump up against planetary sustainability limits. The area under these curves represents, approximately, the total amount of global economic activity, for example for the year it shows. Unless we can break the strong link between economic activity and material throughput, if the area under the curve grows too big, we will push through the safe and sustainable limits of our planet. We currently have a situation of unburnable carbon, which gave rise to the 'keep it in the ground' campaign from the Guardian. How long before we might need an 'unspendable money' campaign? Last night I went to the public launch of 1.5 Degrees: Meeting the challenges of the Paris Agreement - http://www.1point5degrees.org.uk/

Excellent set of talks, discussions and Q&A on meeting the challenges of keeping global warming to below 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. Will be interested to see the results of the rest of the conference, especially how the matter of global justice is treated, on top of the technical and geopolitical aspects. The pace of modern life in the mainstream is something most have become accustomed to. It has become 'the new norm' and it's part of the system with immense inertia driving us through sustainability boundaries.

This is like our perception when driving. When we drive fast, our brains get accustomed to that speed. It's as if our brains make decisions on less and less information from each object we pass, but turn their attention more to movements and 'strategic' matters such as the next junction or changing conditions. If we're not careful, we maintain this 'mode' even when we slow down, eg to enter a 30- or 20 mile an hour zone. As a result, everything seems to be moving so slowly when we do this, and sometimes it feels like we're going at 10 instead of 30. The natural inclination, if we weren't taking notice of speed limit signs, would be to still be travelling at 40 or 50 but thinking we were travelling at 30. I read about this effect a few years ago, and then consciously looked out for it, checking myself against speed limit signs before arriving in the next speed zone, and realised that it was a real effect. Without having been primed to look out for it, I might never have noticed it. Unsustainability is a little like this. Unless we check ourselves against it, the tendency is for the speed of modern 'developed/advanced' existence, built on efficient systems of exploitation of natural and ecological resources, and grown largely on the back of fossil fuels and a growth model of the economy, to be something we become accustomed to. Any 'slower', more sustainable existence feels too slow to even contemplate. So the mainstream juggernaut ploughs on ... The UK has decided to leave the European Union.

I hope that, in the ways this decision is carried out, those who do it draw on British values and identities that are admired by many around the world - tolerance, compassion, innovation, open-mindedness, free expression, love of diversity and opportunity, humility, respect for others, a spirit of both adventure and co-operation in seeking to solve world problems. This ushers in a period of renegotiation of the relationship between the UK and the rest of Europe. I hope that relationship, even if rocky in the short-term, emerges better - to the mutual benefit of all countries and peoples, in the context of our shared responsibilities for the Global Commons and each other. Planetary problems such as Climate Change and Global Inequalities need planetary solutions. While nation states remain fractured and isolationist, these solutions at a global level become more difficult to achieve. By contrast, as countries find ways to work together, such as with the EU-wide agreements and targets on carbon emissions (20% reductions by 2020), we move closer to global level measures to tackle these complex problems. The same would be true for financial measures such as a World Balance Sheet. With a strong European leadership in this topic, we would be far more likely to find ways to create a standard for multi-national accounting for things like Natural Capital than if each nation of the EU developed and operated an approach independently of the others. A European standard would take us a step closer to a global standard and the creation of a World Balance Sheet written in a financial language that all countries can understand.

This is not an argument for every aspect of governance to be globalised, but only for those aspects of human activity that require a global approach in order to succeed. Governance of human activities that contribute to Climate Change is one such aspect. That’s why the Planetary CFO will be voting for the UK to stay in the EU. The World Balance Sheet will be a while in development. That’s because for almost everyone it is a new idea. They’re not sure how it’s going to work and what the impacts will be. At this stage in its gestation, what’s more important than producing numbers to go in it is agreeing principles by which it will be operated.

One of the first principles is that there will be some asset classes for which asset ownership is strictly defined and transfer or conversion in or out of each of those classes is not allowed. An example is the asset class of “Global Commons”. These are assets such as the air we breathe and the sunlight that falls on the ground. We all share in the benefits of these, and in turn we are part of the ecosystems by which the air and energy (together with other materials and inputs) are converted for other organisms to access and in turn those other organisms convert them back into breathable air, food and so on. In a sense nobody owns these Global Commons, or we all do because we all share them, as necessities of life. There will be some other asset classes on the World Balance Sheet which can be owned by individuals or other entities, bought and sold, converted into other assets etc, providing the World Balance Sheet as a whole, in aggregate and by asset class, is not compromised by such transactions. In a sense, the answer to this is both everybody and nobody. The most valuable assets in the World Balance Sheet will be the global commons - the atmosphere, the ecosystems, the water and carbon cycles etc. Nobody owns them. Even where we have agreed property rights, eg on land, morally the property owners don't actually own the animals that visit the land or make their homes on it. They don't own the air above it or the sunlight and rain that falls on it.

What we need is a Global Governance Body ("GGB"), that would be the custodian of the World Balance Sheet on behalf of humanity. The main role of the GGB would be to ensure proper stewardship of the assets. Another role would be to ensure effective distribution of the essential supplies and services sustainably sourced and provided within the global welfare system, for example under a Global Welfare Insurance Scheme. A third role would be to regulate allowable trade within limits to ensure market forces don't compromise long-tern sustainability of the system of systems on Earth. So perhaps in another sense the GGB would be the owner of the World Balance Sheet, on behalf of us all. Might the United Nations perform this function of GGB? Perhaps. The UK Parliament clearly believes it is making the world a safer place by deciding to authorise air strikes in Syria by UK aircraft. Therefore, under a global system relating to the World Balance Sheet, the costs of those air strikes, in terms of the equipment, staff and logistics etc, should be borne by those who are being made safe. This should also include any damage to infrastructure, and some measure of non-combatants’ deaths, eg in terms of the loss of productive and valued members of the Syrian public. If global welfare insurance existed, then it would be easier to charge the costs of security to those whose security and safety is being maintained, because their global welfare fund would cover the costs. To the extent that this is citizens of Syria, then a bill should be sent to the Syrian Government, who have failed to provide that safety so far. To the extent that it is people in other countries, including Western nations, then they should also receive a bill. The United Nations could act as debt collector. And if Governments like the Syrian one (which would have by far the largest bill) can’t pay, then assets of value in the World Balance sheet (eg sustainably managed land) could be seized by the UN in lieu of payment). In this attached paper, I attempt to reconcile the views of George Monbiot and Dieter Helm on valuing nature, which is often a controversial topic.

|

AuthorThe Planetary CFO - working towards a sustainable World Balance Sheet. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|